Innovation

Key Messages

- Despite a decade or so of innovation agendas and prosperity reports, Canada remains near the bottom of its peer group on innovation, ranking 13th among the 16 peer countries.

- Countries that are more innovative are passing Canada on measures such as income per capita, productivity, and the quality of social programs.

- So far, there are no conclusive answers—or solutions—to Canada’s poor innovation ranking.

Innovation Indicators

Putting innovation in context

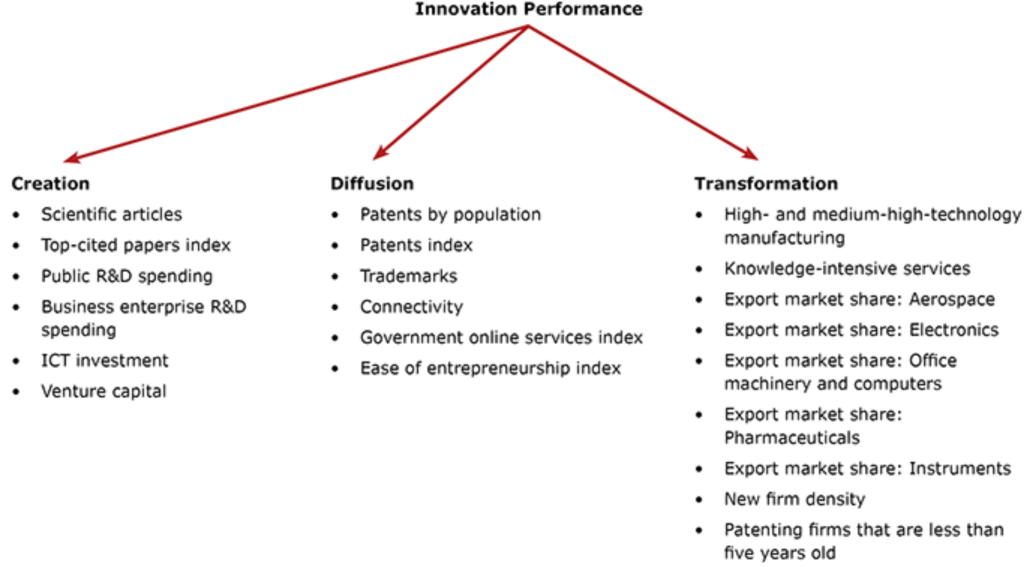

The Conference Board defines innovation as a process through which economic or social value is extracted from knowledge—through the creating, diffusing, and transforming of ideas—to produce new or improved products, services, processes, strategies, or capabilities.

Countries with the highest overall scores have successfully developed national strategies around innovation, giving them a substantial lead over their peers in one or more areas. Ireland has seen enormous success as a host for leading innovative companies. The U.S. fosters a combination of top science and engineering faculties, broad and deep capital markets, and an entrepreneurial culture. Japan is committed to efficient manufacturing and new product development. Switzerland, the top-ranked country this year, is a leader in the pharmaceuticals industry.

Canada is well supplied with good universities, engineering schools, teaching hospitals, and technical institutes. It produces science that is well respected around the world. But, with some exceptions, Canada does not take the steps that other countries take to ensure research can be successfully commercialized and used as a source of advantage for innovative companies seeking global market share. Canadian companies are thus rarely at the leading edge of new technology and too often find themselves a generation or more behind the productivity growth achieved by global industry leaders.

Centre for Business Innovation (CBI)

The Conference Board of Canada has established the Centre for Business Innovation (CBI) as a five-year initiative to help bring about major improvements in firm-level business innovation in Canada.

How is innovation measured?

The Conference Board reports on innovation performance for Canada and 15 peer countries. We use a total of 21 indicators to measure innovation performance. The indicator choice was guided by the Conference Board’s definition of innovation as a process through which economic or social value is extracted from knowledge—through the creating, diffusing, and transforming of ideas—to produce new or improved products, services, processes, strategies or capabilities.

What’s new in this year’s report card?

Two important updates were made to our Innovation report card this year.

First, Italy was dropped from the Innovation report card because its income per capita is not high enough anymore for it to be considered a peer country under our methodology. While Italy has already been included in the most recent updates for the Health, Environment, and Society report cards, it is not included in this report card or in the recent Education and Skills and Economy report cards.

Second, the list of indicators in the Innovation report card also changed. Two indicators—technology exchange and share of world patents—were dropped from our analysis because they were judged to be of little use to either assessing or analyzing innovation performance. Eleven new indicators were added this year:

How does Canada perform on innovation overall?

Despite a decade or so of innovation agendas and prosperity reports, Canada remains near the bottom of its peer group on innovation, ranking 13th among the 16 peer countries.

This does not mean that Canadian inventions are themselves inferior. In fact, Canada produces some great inventions and inventors.

Canada’s low relative ranking means that, as a proportion of its overall economic activity, Canada does not rely on innovation as much as some of its peers.

Does Canada’s low ranking matter?

Innovation is essential to a high-performing economy. Overall, countries that are more innovative are passing Canada on measures such as income per capita, productivity, and the quality of social programs. It is also critical to environmental protection, a high-performing education system, a well-functioning system of health promotion and health care, and an inclusive society. Without innovation, all these systems stagnate and Canada’s performance deteriorates relative to that of its peers.

Canada has been slow to adopt leading-edge technologies. This is problematic, since innovative products have increasingly short cycles. Often within a couple of years of introduction, products are upgraded or must be replaced. In these circumstances, slow adopters never catch up; they are always at least one generation behind the advancing frontier of possibilities that new technology represents. That is not a winning formula, and Canada finds itself playing catch-up on too many technologies.

The problem shows itself in Canada’s relatively low productivity level. As other countries develop and adopt more innovation-related business methods, their companies are gaining in productivity more rapidly than Canadian companies. With new key players—such as China, India, and Brazil—in the global economy, Canadian businesses must move up the value chain and specialize in knowledge-intensive, high-value-added goods and services. Although Canada has some leading companies that compete handily against global peers, its economy is not as innovative as its size would otherwise suggest.

Does Canada do well on any innovation indicators?

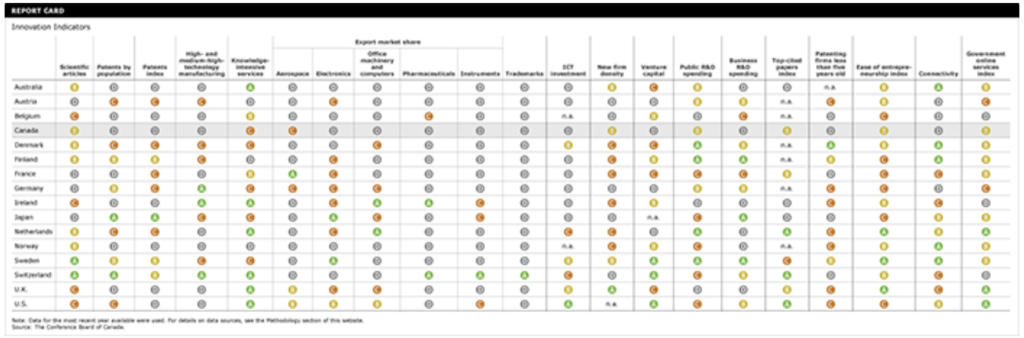

Canada performs poorly on most indicators, scoring 13 “D”s, 2 “C”s, 6 “B”s, and no “A”s. The “D” grades underline Canada’s relative weakness in all three categories of the innovation process—creation, diffusion, and transformation.

Switzerland is an example of a success story. It was the top-performing country, scoring nine “A”s and ranking first on four indicators. Switzerland’s research and leadership in patents and trademarks translate into expertise in knowledge-intensive service, and further to export leadership in pharmaceuticals and scientific instruments. The U.S. is a leader on ICT investment and venture capital investment. It succeeds in translating new knowledge into business value—garnering “A”s or “B”s on knowledge-intensive services, aerospace exports, electronics exports, and office machinery and equipment exports.

The report cards reveal that it takes more than just one or two above-average scores to be a leader—it takes coherence. Coherence distinguishes the leaders from the mediocre. Canada’s peers demonstrate that coherence is a management challenge, not just a technological one.

Why does Canada rank so low on innovation?

Many explanations for poor innovation performance have been proposed over the years by academics, industry groups, think-tanks, and government bodies. Most have focused on public policies, such as taxation, R&D tax credits, and regulations, or on market structural issues. Some organizations have argued that there is a lack of sufficient risk capital, scientists, engineers, or qualified business managers. Others have looked at firm and entrepreneurial behaviour, such as management reluctance to take risks or to build globally competitive large corporations. But these studies have been limited by a lack of sufficient data and information. Consequently, more conclusions have been reached based on beliefs and opinions than on actual evidence.

Where and how to take action? Some major attempts at solutions have already been tried. For example, great progress has been made in reducing the business tax burden in recent years. However, we have not seen hoped-for gains in business innovation performance. Is it because the tax changes were not focused on innovative firms? Did regulatory and other public policy roadblocks get in the way? Did Canadian firms fail to adapt quickly enough to the forces of globalization by internationalizing their business through the development of global value chains and greater openness to the use of foreign direct investment? Or is it because there are internal issues within Canadian firms that are preventing them from taking advantage of lower taxes to become more innovative?

Currently, firms appear to be under-investing in innovation-related technologies. For example, investments in information and communication technologies—“embodied innovations”—have lagged in Canada compared with the United States, and there is evidence that these investments boost productivity. So why are we not seeing more Canadian businesses investing in these technologies— especially given the strong Canadian dollar and growing global competition?

So far, there are no conclusive answers—or solutions—to these firm-level issues. A major roadblock for business and government is the lack of comprehensive data and information for diagnosing the problem. Once that solid evidence is obtained, the next steps will be to create firm-level strategies and reinvigorate the policy environment to encourage firms to innovate.

To help bring about major improvements in firm-level business innovation in Canada, The Conference Board of Canada has established the Centre for Business Innovation (CBI).

Interested in learning more about Canada’s innovation ranking?

Who Dimmed the Lights? Canada’s Declining Global Competitiveness Ranking (Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2012).

Is there a problem with the way business innovation is financed in Canada?

Innovative firms frequently cite finance as an important issue. In a survey by the Conference Board’s Centre for Business Innovation (CBI), 25 per cent of respondents identified finance as their number one innovation challenge.1 As companies move along the continuum from new product development to commercialization, finances are often strained, which may be one reason for Canada’s relatively poor commercialization track record.

That same CBI survey revealed that firms often finance innovation through internal cash flow and that internal cash flow is the biggest financial barrier to innovative activity. This is typical of the Canadian innovation challenge: great people, great ideas … poor commercialization.2

CBI research has outlined a number of mechanisms to help improve business capabilities around commercialization:3

- In some instances, capital markets can lead company transformations. Canadian innovators should look outside, as well as inside, the country for finance and financing expertise.

- Multinationals are transforming their traditional hub-and-spoke models into global value chains. Canadian subsidiaries need to make the case for Canada in this evolving model.

- Canadians need to recognize that a healthy merger-and-acquisition marketplace is a key part of innovation finance.

- Canada’s large pension plans should consider making larger investments in private equity and other alternative asset classes.

- SMEs could benefit from tools and expert advice to help them develop effective pitches and successfully access capital from potential investors.

- Universities should take a leadership role in developing individuals with both specialized financial analysis skills and expertise in managing commercialization.

- Canada’s business culture needs to focus more on growth through innovation and less on sales to other companies.

- Canada successfully funds risky ventures in mining and oil and gas development. The financing techniques used by these firms need to be adopted in non-traditional areas, such as biotech and clean energy.

Interested in learning more about innovation finance?

Financing Innovation by Established Businesses in Canada (Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2012).

How does Canada’s capacity to innovate compare with the 16-country average?

The radar diagram below is a snapshot of Canada’s innovation performance (and the 16-country average performance) relative to that of the best-performing peer country (the outer ring) for each of the 21 innovation indicators. The chart has 21 axes—one for each indicator—that radiate out from the centre. A score closer to the centre represents a worse performance, while a score closer to the outer circle represents a better performance.

Canada is above the 16-country average on only six indicators: top-cited papers, ease of entrepreneurship, government online services, new firm density, scientific articles, and aerospace exports. It is about average on public R&D spending. Canada is well below average on the remaining 14 indicators, ranking in second-to-last spot on venture capital investment.

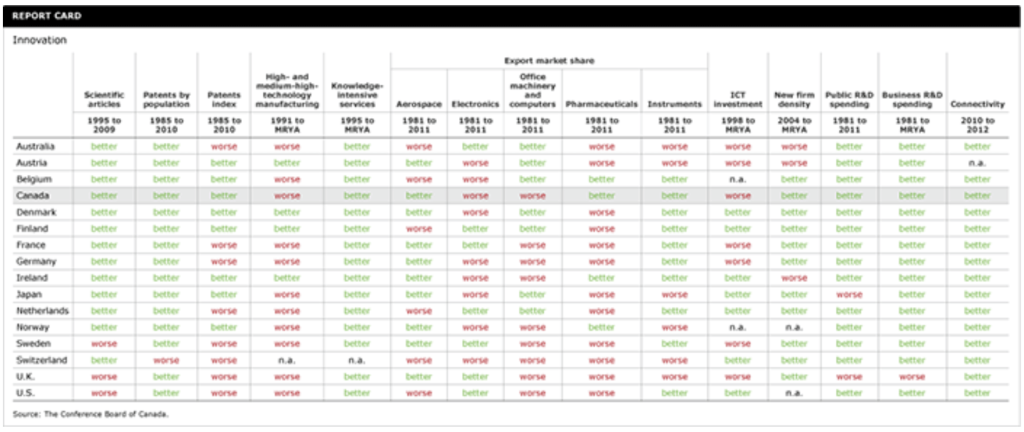

Has Canada’s innovation record improved?

In an absolute sense, Canada’s record improved on 11 indicators for which historical data are available. However, because other countries also improved, the gains were not enough to move Canada up in the rankings. So in a relative sense, Canada remains a “D” performer.

Footnotes

1 Michael Grant, Financing Innovation by Established Businesses in Canada (Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2012), i.

2 Ibid., ii.

3 Ibid., ii.