Ease of Entrepreneurship Index

Key Messages

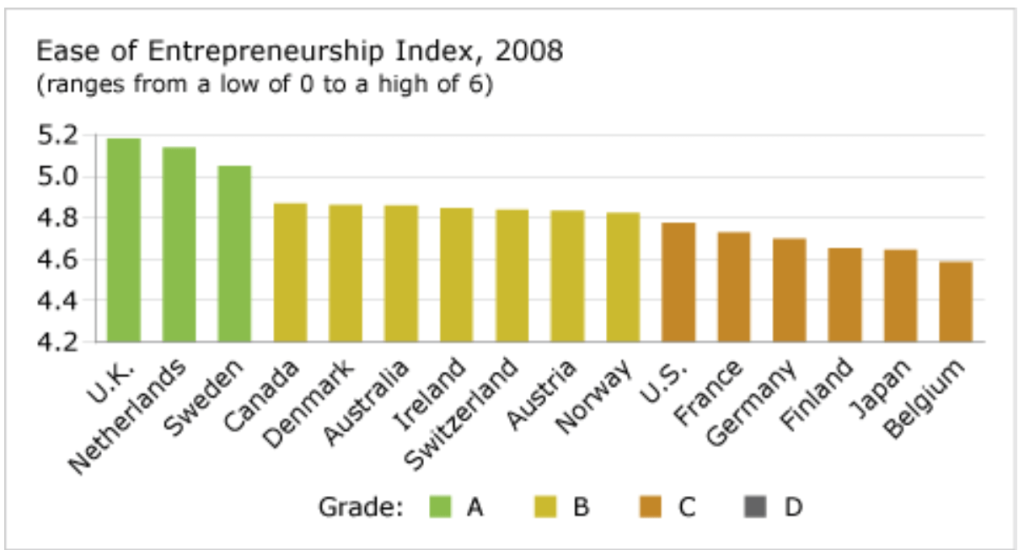

- Canada gets a “B” and ranks 4th out of 16 countries.

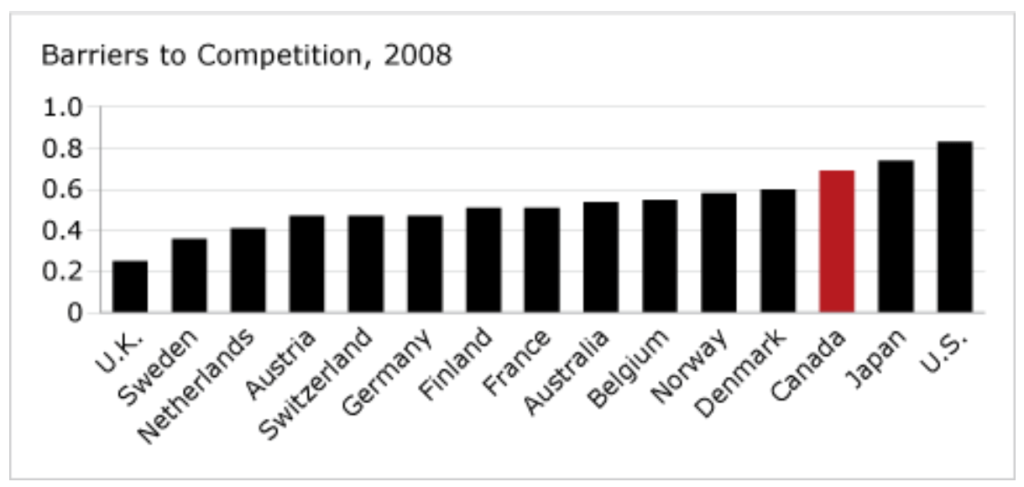

- Canada has relatively low regulatory and administrative barriers to entrepreneurship, but ranks a poor 13th out of 15 countries in addressing barriers to competition—a key determinant of innovation success.

- To improve, Canada should focus on reducing barriers to competition while maintaining or enhancing the regulatory and administrative environment for entrepreneurship.

Why is ease of entrepreneurship important to innovation?

Entrepreneurship and innovation are tightly intertwined. Start-up firms tend to emerge and depend for their success on the development and commercialization of new or improved products or services. Unleashing and improving innovation requires an environment that enables entrepreneurship.

How effective countries are in reducing the barriers to entrepreneurship has an important impact on their innovation performance. When entrepreneurs or potential entrepreneurs face high barriers, fewer businesses will form, succeed, and contribute to innovation and commercialization success. Indeed, as the OECD notes, “for businesses to enter the market and grow they need a suitable regulatory framework.”1

Countries that aim to facilitate and support entrepreneurship must create a competitive environment—which the Council of Canadian Academies’ Expert Panel on Business Innovation concluded is “among the most potent incentives for innovation”2

—and minimize regulatory and administrative burdens. In particular, entrepreneurship is enabled when countries minimize:

- “barriers to competition (e.g., legal barriers, antitrust exemptions, barriers in network sectors, and in retail and professional services);

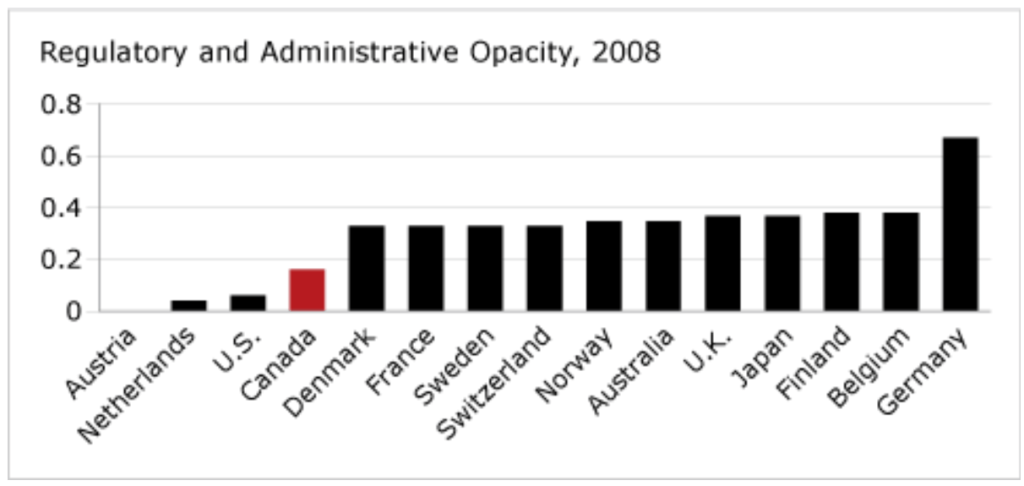

- regulatory and administrative opacity (e.g., licenses, permits, simplicity of procedures); and

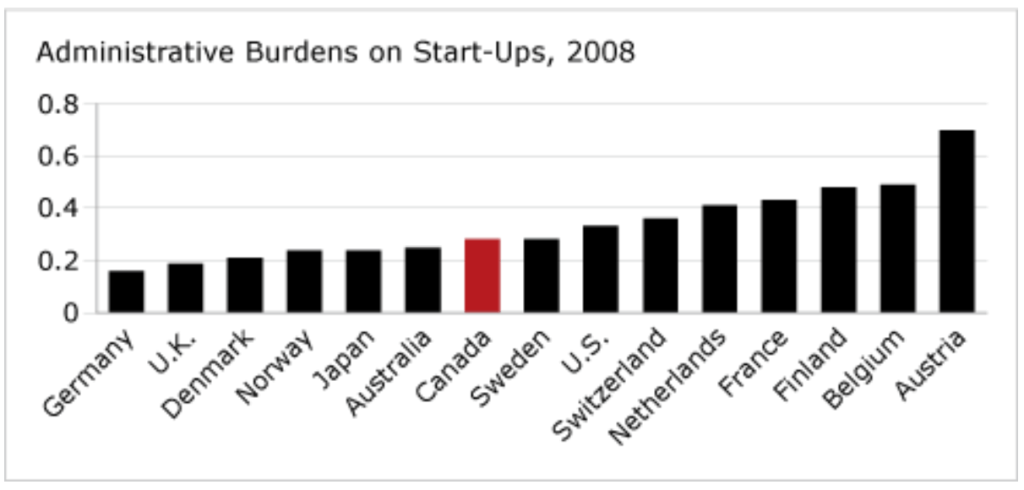

- administrative burdens for creating new firms.”3

How are grades assigned for this report card?

The ease of entrepreneurship index score is calculated by summing the scores on the three components (barriers to competition, regulatory and administrative opacity, and administrative burdens for creating new firms) and subtracting that sum from 6. For example, Canada scores 0.69 on the barriers to competition component, 0.16 on regulatory and administrative opacity, and 0.28 on administrative burdens for creating new firms. These three components add to 1.1 which, when subtracted from 6, results in an ease of entrepreneurship index score of 4.9.

Because all peer countries have relatively high scores, no country was deemed a “D” performer. Instead of dividing the countries into four groups (A-B-C-D), we divided them into three groups (A-B-C) using the following method:

- We calculated the difference between the best and worst score on the ease of entrepreneurship index and divided this figure by 3.

- A country received a report card rating of “A” if its ease of entrepreneurship index was in the top third (an index score of 4.985 to 5.194), a “B” if its index score was in the second third (an index score of 4.785 to 4.984), and a “C” if its index score was in the bottom third (an index score of 4.586 to 4.784).

How does Canada’s performance compare to its peers?

Canada achieves a grade of “B” and ranks 4th out of 16 countries on the ease of entrepreneurship report card. Given that nearly all of the countries examined perform well on ease of entrepreneurship—and the difference in score between the top- and bottom-ranked countries is relatively small—the rankings should not be treated with either fanfare or hand-wringing. In fact, all 16 countries examined by the Conference Board either meet or exceed the average score of 4.6 for the 43 countries the OECD reported on—indicating a very strong cohort.

Still, the overall score is an aggregate of scores on three specific sub-indicators—namely, barriers to competition, regulatory and administrative opacity, and administrative burdens for creating new firms—and Canada’s performance on each of these varies considerably. Note that lower values suggest lower barriers.

On barriers to competition, Canada finds itself ranked much lower—13th out of 15 countries—than its overall 4th place ranking would predict. This is especially worrying given the central importance of competition to innovation performance.

On regulatory and administrative opacity, Canada fares much better, with a 4th-place ranking that equals its overall score.

Canada’s performance with respect to the administrative burdens on start-ups component earns it a middling rank of 7th out of 15 countries.

Thus, although Canada maintains a high overall ranking on ease of entrepreneurship, there is reason for some concern about barriers to starting up a company and, especially, the nature of the competitive environment.

Who are the leaders in this report card?

No country performs consistently well across all three sub-indicators that make up the ease of entrepreneurship report card. This helps to explain why there is little variation in the overall scores. The U.K., for example, achieves its overall 1st-place ranking on the basis of a 1st in barriers to competition and 2nd on administrative burdens on start-ups. But it ranks a much lower 11th on regulatory and administrative opacity. Similarly, although the Netherlands ranks 2nd overall, primarily thanks to a 2nd in regulatory and administrative opacity and a 3rd in barriers to competition, it manages only an 11th in administrative burdens on start-ups.

A strong performance in the overall rankings, then, can hide weakness in at least one of the three components. In fact, only one country—Sweden—manages to achieve rankings in at least the top 8 in all three components. Every other country faces a ranking of 10th or worse on at least one component. Still, the differences in the overall scores between these 16 countries are small and meet or exceed the OECD average, something that speaks to the generally strong performance of the peer group overall.

What can Canada do to improve its grade?

Although Canada achieves a fourth-place ranking and provides an enabling environment for entrepreneurship, there is room for improvement. In particular, Canada should focus its attention on reducing barriers to competition—the sub-indicator on which it ranks lower than most of its international competitors. Action to enhance fair competition in the Canadian economy should be an innovation policy priority in light of the evidence showing that competition is a key driver of innovation performance.4

Indeed, ensuring that most sectors of the Canadian economy achieve and maintain appropriately competitive levels of market concentration and market entry can provide the incentives to spur innovation among new and existing firms.

Footnotes

1 OECD, OECD Science, Technology, and Industry Outlook 2012 (Paris: OECD, 2012), 421.

2 Council of Canadian Academies, Innovation and Business Strategy: Why Canada Falls Short—Report of the Expert Panel on Business Innovation (Ottawa: Council of Canadian Academies, 2009), 109. See the full discussion in Chapter 6 of the report.

3 OECD, OECD Science, Technology, and Industry Outlook 2012 (Paris: OECD, 2012), 421.

4 Council of Canadian Academies, Innovation and Business Strategy: Why Canada Falls Short—Report of the Expert Panel on Business Innovation (Ottawa: Council of Canadian Academies, 2009), 109–118.