Students with High-Level Science Skills

Key Messages

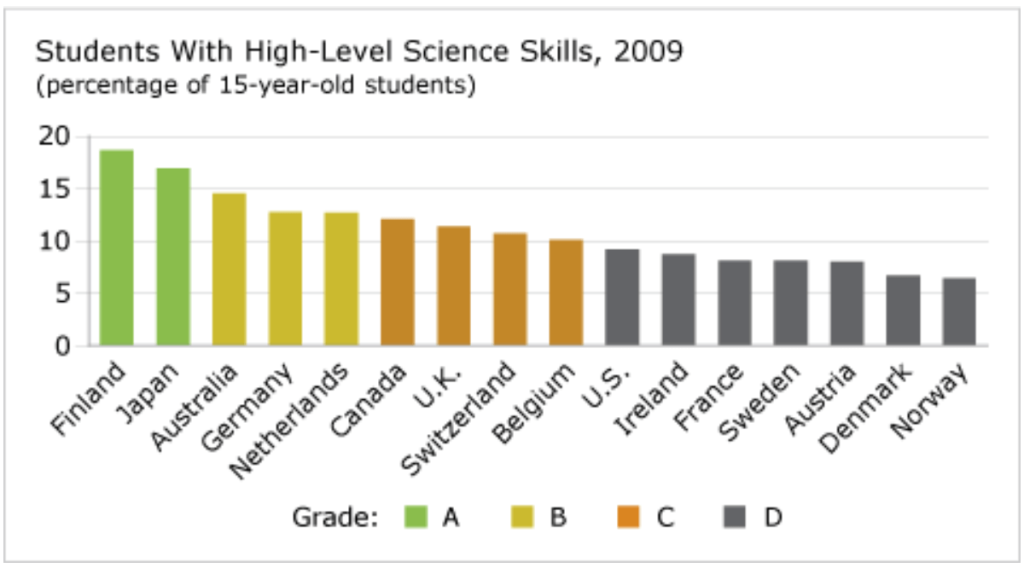

- Canada gets a “C” grade and ranks 6th out of 16 peer countries.

- Science skills are important for all students, not just those aspiring to a career in the sciences.

- High-level science competencies are critical for the creation of new technology and innovation.

Putting student science skills in context

The growing role of science, math, and technology in everyday life means science skills are important for all students, not just those aspiring to a career in the sciences. This is a significant shift from the past, when school mathematics curricula were dominated by the need to provide the foundations for the professional training of a small number of mathematicians, scientists, and engineers.1

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is an international assessment of the skills and knowledge of 15 year olds, coordinated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). It assesses whether students approaching the end of compulsory education have acquired the knowledge and skills essential for full participation in society.

The science component of the PISA test gauges the extent to which students have learned fundamental scientific concepts and theories. It also measures the capacity of students to identify scientific issues, explain phenomena scientifically, and use scientific evidence as they encounter, interpret, and solve real-life problems involving science and technology. This approach reflects the reality of how globalization and computerization are changing societies and labour markets.

Basic competencies in science are generally considered essential to be able to use new technology, while high-level competencies are critical for the creation of new technology and innovation. This makes the acquisition of science skills through the core education system integral to a country’s ability to be successful in the new knowledge economy.

How do the high-level science skills of Canadian students compare to those of Canada’s peers?

Canada ranks in 6th place among the 16 peer countries in high-level science skills. Just over 12 per cent of Canadian students scored at level 5 or 6 on the PISA assessment. This gives Canada a “C”. Finland was the best performer on student science skills; nearly 19 per cent of its students had high-level skills. Canada did a better job in limiting the proportion of students with low-level science skills than it did in producing students with high-level skills.

Has Canada succeeded in increasing its share of students with high-level science skills?

The share of students with high-level science skills dropped in 7 of the 15 peer countries with comparable results in the 2006 and 2009 assessments. The deterioration in performance caused three of these countries—Canada, Ireland, and the United Kingdom—to move down a grade. Canada’s grade dropped from a “B” on the 2006 science test to a “C” on the 2009 test.

Two countries—Germany and Japan—had relatively strong increases in the share of students with high-level science skills, resulting in these countries moving up a grade.

What kind of science skills are needed in the workplace?

The Conference Board has developed a tool to help Canadians understand the science competencies they need to participate fully in the world of work.

Science Literacy for the World of Work: Skills Profile (PDF), Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada.

What can Canada do to improve student science skills?

In 2001, the Conference Board conducted a case study on Let’s Talk Science, a national charitable organization striving to improve scientific literacy through innovative educational programs, research, and advocacy. Understanding how people learn science and how science programs affect children and educators helps Let’s Talk Science develop and deliver the best possible programs, workshops, and activities.

Interested in learning more about Let’s Talk Science?

Let’s Talk Science: Making Science Education Exciting, Relevant and Rewarding, Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2001.

Footnotes

1 OECD, Learning for Tomorrow’s World: First Results from PISA 2003 (Paris: OECD, 2004), 37.

2 Although the OECD conducted its first student science test in 2000, data on the shares of high- and low-skilled students are not available from that assessment.