Students with Low-Level Math Skills

Key Messages

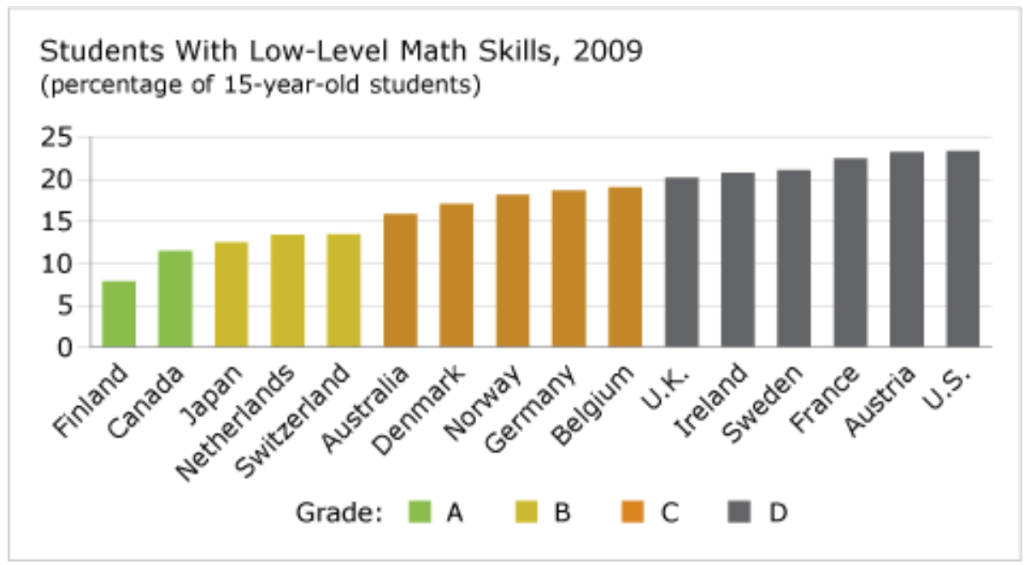

- Canada earns an “A” grade and ranks 2nd out of 16 peer countries.

- Although the proportion of students with low-level math skills has increased slightly since 2003, Canada has maintained its “A” grade in the Conference Board’s rankings.

- PISA performance in mathematics is closely related to subsequent educational outcomes.

Putting student math skills in context

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is an international assessment of the skills and knowledge of 15 year olds, coordinated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). It assesses whether students approaching the end of compulsory education have acquired the reading, math, and science skills that will help them to succeed in life.

The OECD defines math skills as “an individual’s capacity to formulate, employ and interpret mathematics in a variety of contexts. This includes reasoning mathematically and using mathematical concepts, procedures, facts and tools to describe, explain and predict phenomena. Mathematical literacy also helps individuals recognise the role that mathematics plays in the world and make the well-founded judgements and decisions needed by constructive, engaged and reflective citizens.”1

In its report on the 2006 PISA results, the OECD outlines the importance of math skills in today’s world:

With the growing role of science, mathematics and technology in modern life, the objectives of personal fulfilment, employment and full participation in society increasingly require that all adults, not just those aspiring to a scientific career, should be mathematically, scientifically and technologically literate. The performance of a country’s best students in mathematics and related subjects may have implications for the role that that country will play in tomorrow’s advanced technology sector, and for its overall international competitiveness. Conversely, deficiencies among lower-performing students in mathematics can have negative consequences for individuals’ labour-market and earnings prospects and for their capacity to participate fully in society.2

An outstanding issue is whether good results on the PISA math tests set students on a path to pursue advanced credentials in related fields. Over time, we might expect to see a relationship between these scores and the number of graduates in science, math, computer science, and engineering.

How do the low-level math skills of Canadian students compare to those of Canada’s peers?

Nearly 11.5 per cent of Canadian students scored at level 1 or below on the 2009 PISA math test. This shows that only a small percentage of Canadian 15 year olds are not acquiring basic math skills through the core education system. Canada places 2nd out of 16 peer countries in the Conference Board comparison and gets an “A” grade.

Finland is in 1st place; only 8 per cent of Finnish students scored low on the PISA math test in 2009. The U.S. places last in our rankings, with 23 per cent of its students scoring at level 1 or below on the PISA math test.

Has Canada been able to decrease the proportion of students with low-level mathematics skills?

Five of the 14 peer countries with comparable results in the 2003, 2006, and 2009 assessments show a decrease in the share of students with low-level math skills: Germany, Japan, Norway, Switzerland, and the United States. The improvement, however, was not enough to move any of them up a grade.

Nine countries—including Finland and Canada, the two “A” performers—saw performance deteriorate, with an increase in the share of students with low-level math skills. This deterioration caused six of those countries—Belgium, Denmark, France, Ireland, Netherlands, and Sweden—to drop a grade. Both Finland and Canada maintained their “A” grades.

Do PISA math test results predict future educational success?

Results from the Youth in Transition Survey, by Statistics Canada, show a positive relationship between the math skills of 15-year-old students and the likelihood of completing further education. The effects of improving math skills are “in most cases statistically significant and also quantitatively important.”3

There were, however, gender differences. For females, the effect of improving math skills had a stronger positive effect on high-school completion. For males, the effect was strong on completing some post-secondary education.4

Footnotes

1 OECD, PISA 2009 Results: What Students Know and Can Do—Student Performance in Reading, Mathematics and Science. Volume I (Paris: OECD, 2010), 122.

2 OECD, PISA 2006: Science Competencies for Tomorrow’s World, Volume 1: Analysis (Paris: OECD, 2007), 322-23.

3 OECD, Pathways to Success: How Knowledge and Skills at Age 15 Shape Future Lives in Canada (Paris: OECD, 2010), 67.

4 OECD, Pathways to Success: How Knowledge and Skills at Age 15 Shape Future Lives in Canada (Paris: OECD, 2010), 67.