Homicides

Key Messages

- Canada scores an “A” even though it ranks 15th out of 17 peer countries.

- If the U.S.—which has an extraordinarily high homicide rate—were removed from the analysis, Canada would get a “C” grade.

- Canada’s homicide rate is five times that of Japan and the U.K., the best performers on this indicator.

Putting the homicide rate in context

A sense of personal and community safety is essential to a high quality of life. Physical, psychological, and financial effects of crime reduce levels of trust within a society and therefore have an impact on social cohesion. Breakdown in social cohesion is thus measured most directly by assessing levels of crime.

The Conference Board ranking analyzes statistics on crime against people (homicide rates) and against property (burglary rates). Both forms of crime can have a major impact on the well-being of victims and on the wider society.

The total social and economic costs of Criminal Code offences in Canada were $31.4 billion in 20081—or $943 per capita—according to a 2012 study for the Department of Justice. This figure includes:

- $15 billion in costs for the Canadian criminal justice system (such as policing and court costs)

- $14.3 billion in costs borne by the victims (such as medical costs, lost wages, and stolen property)

- $2.1 billion in third-party costs (such as costs to other people hurt during the crime, as well as costs to run programs such as shelters, victim services, and crime prevention)

Reducing crime would free up funds for other programs that could improve productivity and competitiveness—such as education, skills training, health, or advancements in innovation and technology.

How does Canada’s homicide rate compare to those of peer countries?

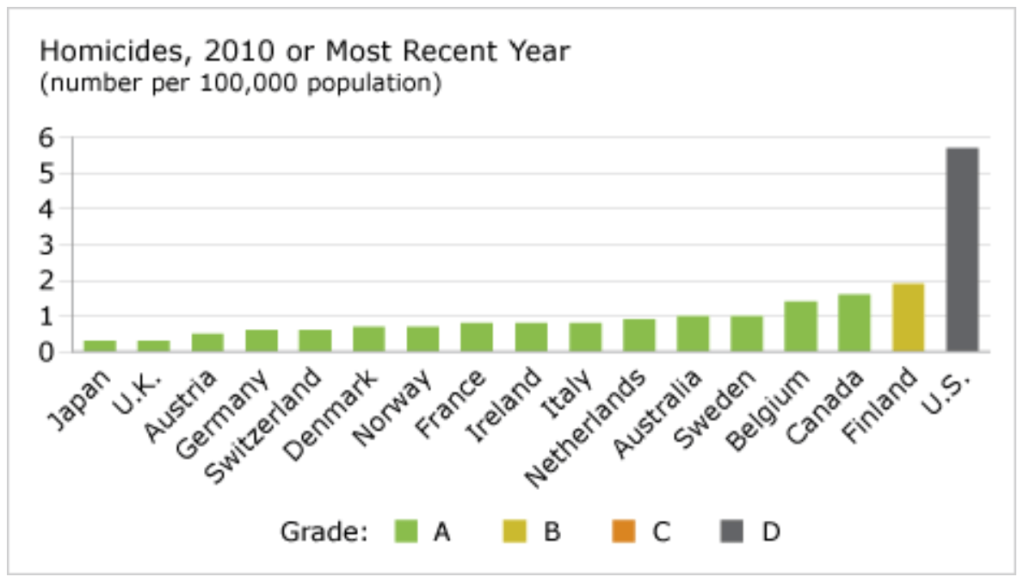

Canada’s homicide rate is 1.6 deaths per 100,000 people. This rate is five times that of the best performers, Japan and the United Kingdom. Canadians may take comfort in the fact that Canada’s homicide rate is drastically lower than that of the U.S. (5.7 deaths), but Canada’s “A” grade is distorted by that country’s extraordinarily high homicide rate.

All peer countries except Finland and the U.S. earn “A”s on this indicator. To put Canada’s relative performance in perspective, 14 of Canada’s peer countries have lower homicide rates than Canada.

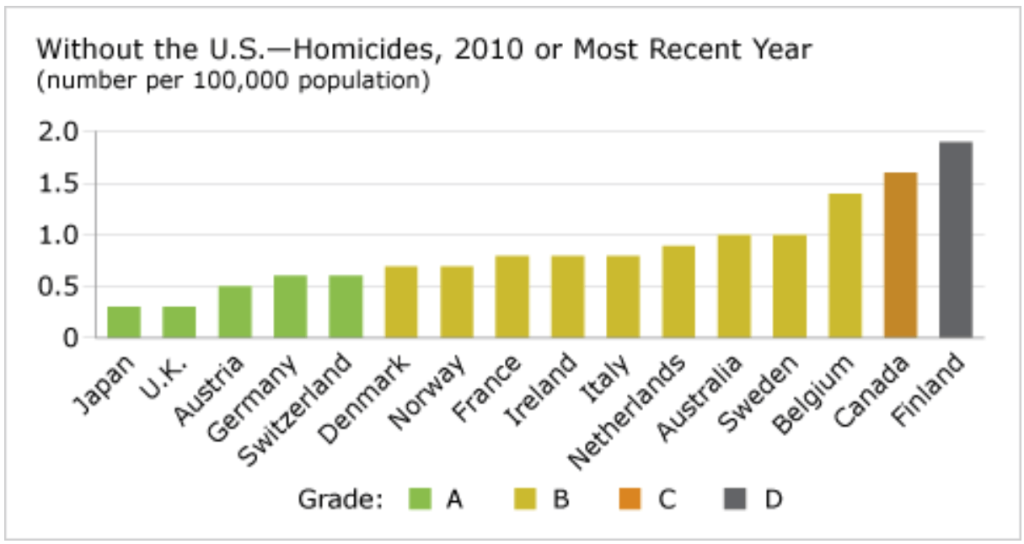

If the U.S. were removed from the analysis, ten of the peer countries—including Canada—would lose their “A” grades. Canada would earn a “C,” which is perhaps a fairer assessment of Canada’s relative performance.

Has Canada’s homicide rate improved?

Canada’s homicide rate has been declining since the mid-1970s, from a peak of 2.8 deaths in 1975 to 1.6 deaths in 2009. Most peer countries have also experienced a decrease in their homicide rates.

Statistics Canada’s 2009 General Social Survey reported that 93 per cent of Canadians aged 15 and over were satisfied with their personal safety from crime; only slightly lower than in 2004 (94 per cent).2

Has Canada improved its relative grade?

With the U.S. distortion, all the peer countries—except the U.S. and Finland—received “A” grades for the past five decades.

A more nuanced picture is obtained if the U.S. is removed from the picture. Only Denmark, Norway and the U.K. remain consistent “A” performers over the past five decades, while Canada’s average relative grade drops to a “C” for three of the five decades.

With the U.S. out of the ranking, Finland becomes the only “D” performer. Finland has had an exceptionally high homicide rate relative to other western European countries for most of the 20th century and the first decade of this century.

The Finnish homicide rate should come with a caveat related to the reasons behind the homicide and the method used in the crime, according to a recent joint study by Finnish National Research Institute of Legal Policy, the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention, and the Dutch Leiden University.3 Only 6 per cent of Finland’s homicides relate to criminal activities—compared with 30 per cent in the Netherlands, where 35 per cent of the homicides were committed by shooting and 38 per cent occurred outdoors. By contrast, most of Finland’s homicides involved alcohol, where the victim and the killer knew one another and the homicide took place in a private residence, often with a kitchen knife. In the Netherlands, the victim and killer rarely knew one another.

What can Canada do to reduce crime?

Although many still believe that “cracking down on crime” is the best way to protect communities, a 2008 Conference Board report found that other forms of crime prevention produce better results. In particular, approaches that address the root causes of crime are proving to be the most successful. An analysis of successful programs in Canada, the U.S., and the U.K. yielded the following recommendations:

- Begin with an understanding of the community and its problems.

- Develop programs and policies to deal with these problems in their community context, and focus on crime reduction.

- Learn from and build on successful prevention programs developed elsewhere.

- Stay focused—prevention programs will not succeed without a great deal of effort.

- Secure commitment from senior government officials.

- Provide adequate resources.

- Ensure cooperation and coordination among organizations targeting crime reduction.

- Take a comprehensive approach to prevention and develop multi-faceted strategies.

Learn more about crime reduction programs:

Making Communities Safer: Lessons Learned Combatting Auto Theft in Winnipeg, Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2008.

Footnotes

1 Department of Justice Canada, “Costs of Crime in Canada, 2008” (accessed October 30, 2012).

2 Statistics Canada, “Canadians’ Perceptions of Personal Safety and Crime, 2009,” Juristat, December 2011, Catalogue no. 85-002-X (accessed October 30, 2012).

3 National Research Institute of Legal Policy, National Council for Crime Prevention, and Leiden University, Homicide in Finland, the Netherlands and Sweden: A First Study on the European Homicide Monitor Data, 2011 (accessed October 30, 2012).