Use of Forest Resources

Key Messages

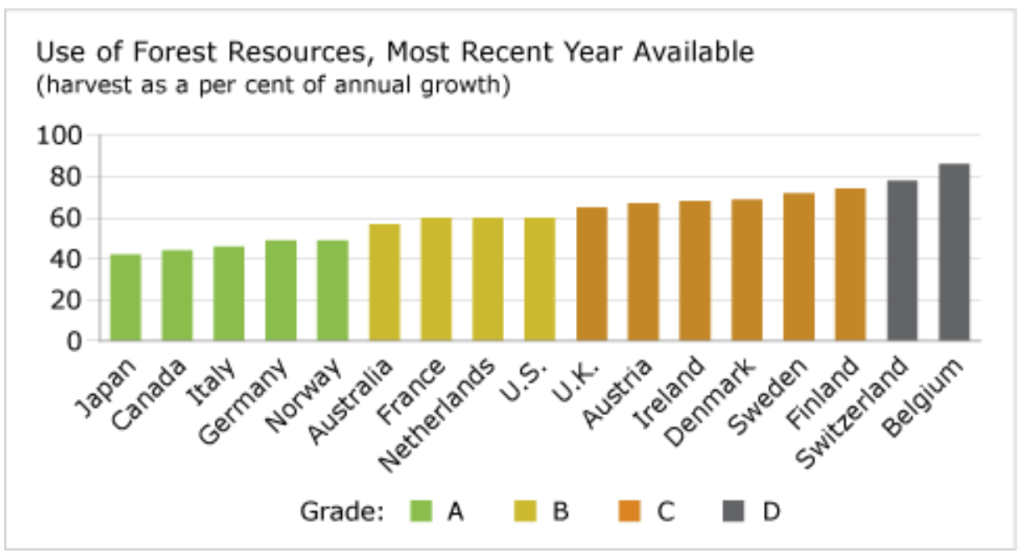

- Canada gets an “A” and ranks 2nd out of 17 countries for the intensity of use of its forest resources.

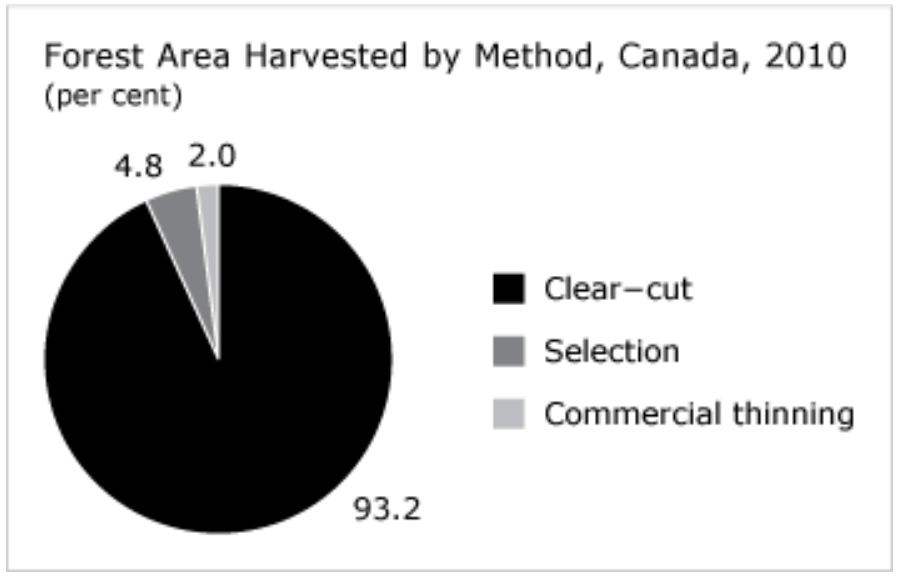

- In Canada, 93 per cent of forest area harvested is clear-cut.

- Most timber harvesting in Canada still occurs in primary or old-growth forests.

Putting intensity of use of forest resources in context

Preserving forests, particularly primary and old-growth forests, is key to preserving biodiversity and contributing to a country’s overall environmental health. The assumption is that the higher the percentage of timber cut relative to forest growth, the greater the stress on the forest environment. The relationship between timber cut and the renewal of timber stocks is a central concern of sustainable forest resource management.

How does Canada’s intensity of use forest resources compare to that of other countries?

Canada ranks 2nd out of 17 peer countries for the intensity of use of forest resources (actual harvest as a per cent of annual growth) indicator and receives an “A” grade for performance. In recent years, Canada’s actual harvest has been 44 per cent of annual growth, while the OECD average has been 56 per cent.

Canada’s ranking on this indicator reflects the large volume of forested land in Canada relative to the other OECD countries.1 More than 70 per cent of Canada’s forested area has never been harvested.2 Switzerland and Belgium, for example, received “D”s, harvesting 78 and 86 per cent of their forests’ annual growth, respectively. But the forested area in these countries is substantially smaller than in Canada. Canada is one of the few peer countries to retain a relatively large proportion of its primary forests.

Has Canada’s relative grade changed over time?

Canada achieved an “A” grade for performance on this indicator throughout the 1980s, the 1990s, and this decade. Only Italy can match this performance.

How have Canada’s forest harvesting practices changed over time?

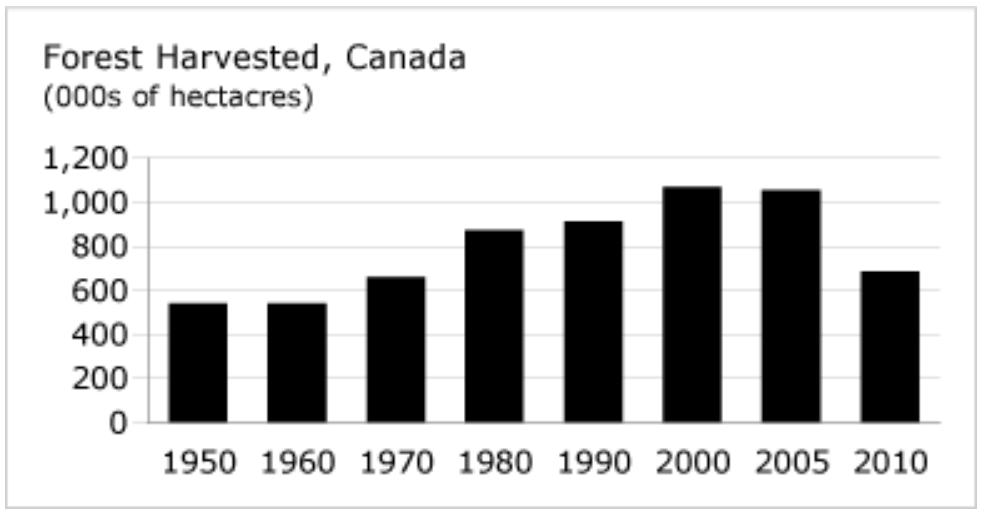

Forest harvests steadily increased from the 1950s to 2005, but have decreased since then. In 2010, just over 687 thousand hectares were harvested in Canada.3 But Canada continues to harvest its unique and biologically diverse old-growth forests, an issue of contention.

Are Canada’s forestry practices more or less sustainable than those in other countries?

In Canada, 93 per cent of the forest area harvested is clear-cut, making clear-cutting the most common harvesting method. Clear-cutting removes most of the trees from an area, while leaving patches of trees and buffers intact. In comparison, the selection system removes single trees or small groups for timber at relatively short intervals to protect the quality and value of the entire forest area.4

Clear-cutting is favoured in Canada’s boreal forest because it resembles natural disturbances such as fire, wind, floods, and insects and allows the forest to regenerate naturally. Harvesting is done in blocks, strips, or patches to mimic natural disturbance patterns. But although clear-cutting allows for forest regeneration, it can also lead to a loss of biodiversity.

Forests are managed by the provinces, and so the size limit of clear-cuts varies across Canada. In Ontario, the size limit of a clear-cut is 260 hectares, compared with 150 hectares in northern Quebec and 100 hectares in central Quebec.5 In B.C., the size limit of clear-cuts has dropped in the last decade from 40 to less than 30 hectares.

In comparison, the Australian state of Tasmania limits clear-cuts to either 50 or 100 hectares, depending on the woodlot’s slope. And there are no clear-cutting rules or guidelines in Finland or the U.S. southeastern states. Other countries such as Japan and Sweden have limited clear-cuts to 20 hectares.

What contributes to sustainability?

With its vast forest land, Canada is in a position to show leadership by preserving its old-growth and primary forests. In eastern North America and Europe, nearly all the primary forests have already been replaced by secondary forests as a result of intensive logging in the 19th century. Consequently, most logging in these countries now occurs in second-growth forests. Ninety per cent of logging in Canada, however, still occurs in primary and old-growth forests, which are rich in biodiversity and wilderness value. Almost 75 per cent of B.C.’s old-growth coastal rainforest has been subject to clear-cutting.6 Canada is in a unique position to preserve its original forests, but it has not yet stepped up to the challenge.

In the Scandinavian countries of Finland, Norway, and Sweden, clear-cutting has almost entirely been abandoned because of intensive forestry practices in the past. To restore the biological integrity of their forests, individual trees and groups of trees (hardwoods, whenever possible) are retained in final felling and left to grow as part of the new stand. Large industrial forest enterprises now leave an estimated 10 per cent of the potential cut standing for ecological reasons. Sustainable forestry practices are a priority for these countries: Over $26 million is invested annually in sustainable forestry research.7

Canada has the world’s largest area of forest certified to third-party sustainable forest certification. Forest certification ensures that harvested areas are reforested, that laws are obeyed, and that no unauthorized logging takes place. Certification also promotes sustainable forest management by ensuring the conservation of biological diversity, the maintenance of wildlife habitat, soils, and water resources, and the sustainability of timber harvesting.

The area of forests certified in Canada has steadily increased in recent years. In 2011, Canada had 150.6 million hectares certified to one of the three programs: the Canadian Standards Association’s Sustainable Forest Management Standard, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) standards, and the Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI).8

Footnotes

1 David Suzuki Foundation, The Maple Leaf in the OECD: Comparing Progress Toward Sustainability (Vancouver: David Suzuki Foundation, 2005), 33.

2 OECD, Environmental Performance Reviews: Canada (Paris: OECD, 2004), 85.

3 Natural Resources Canada, “Annual Harvest of Timber Relative to the Level of Harvest Deemed to Be Sustainable” (accessed November 17, 2012).

4 Canadian Council of Forest Ministers, Harvesting Practices, 2008 (accessed August 20, 2008).

5 Constance L. McDermott et al, A Global Comparison of Forest Practice Policies Using Tasmania as a Constant Case (New Haven: Global Institute of Sustainable Forestry, March 2007), 28.

6 David Suzuki Foundation, Canada‘s Rainforests Status Report 2005 (Vancouver: David Suzuki Foundation, 2005).

7 Faculty of Forestry and the Forest Environment, Lakehead University, Forest Management in Scandinavia (accessed August 20, 2008).

8 Certification Canada, “Statistics” (accessed November 17, 2012).