Health

Stay up to date

Looking for the latest in healthcare planning? Create a CBoC account and sign up for email updates.

Focus area—Health

The data on this page are current as of February 2015.

Key Messages

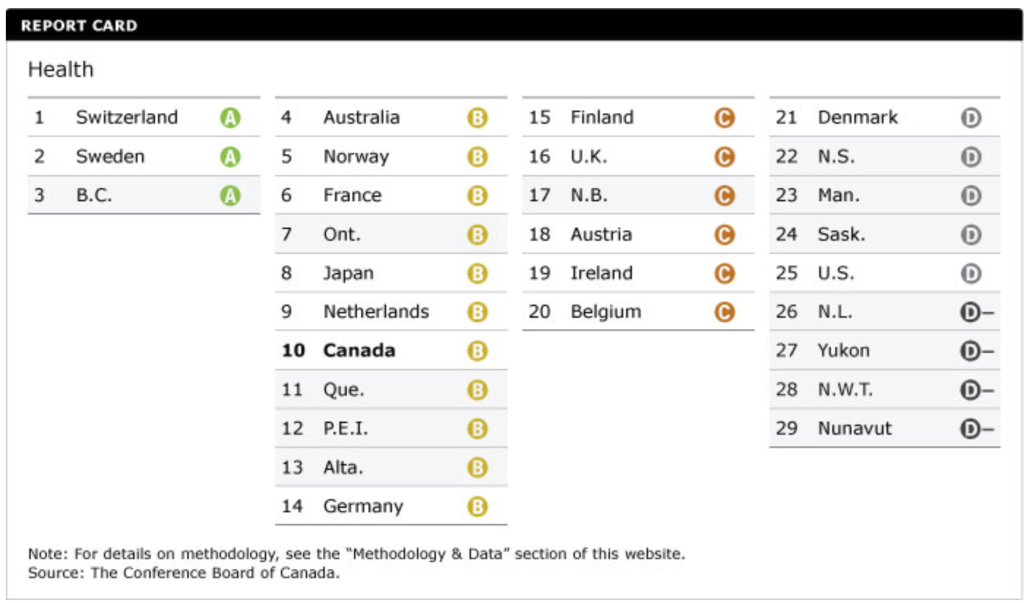

- B.C. is the top-placing province, scoring an “A” on the health report card and ranking third overall, after Switzerland and Sweden.

- Newfoundland and Labrador, the worst-ranked province, scores a “D-” for placing just below the worst-ranking peer country, the United States.

- Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Nova Scotia also do poorly and get overall “D” grades on health.

- The territories have the worst health outcomes in Canada, with Nunavut ranking near or at the bottom on most indicators.

Putting health in context

What is health? For some, health means the absence of disease and pain; for others, it is a general feeling of wellness. The World Health Organization defines health more broadly: “the state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”1

This broad definition aligns with the Conference Board’s overarching goal in benchmarking Canada’s performance—to measure quality of life in Canada and in its peer countries. Most would agree that without health, quality of life is severely compromised.

How is health performance measured?

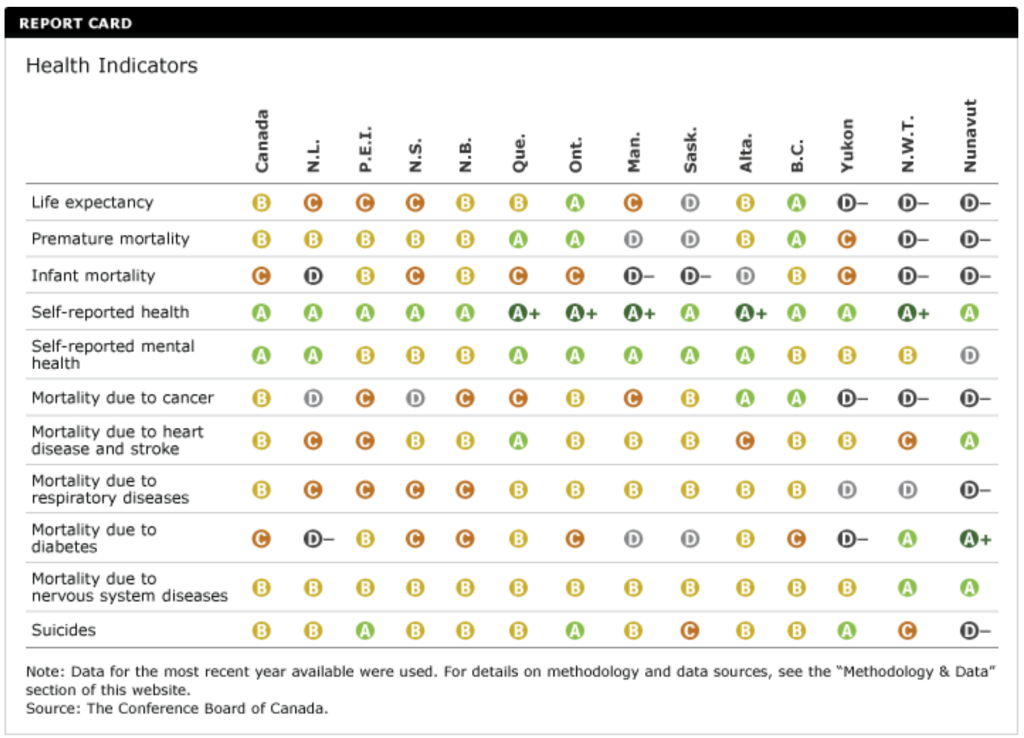

To measure health performance, we evaluate Canada, its provinces and territories, and 15 peer countries2 on the following 10 report card indicators: life expectancy, premature mortality, infant mortality, self-reported health status, mortality due to cancer, mortality due to heart disease and stroke, mortality due to respiratory disease, mortality due to diabetes, mortality due to diseases of the nervous system, and suicides. We also evaluate the performance of the provinces and territories, and Canada’s overall performance, on self-reported mental health. Unfortunately, there are no comparable international data for this indicator.

Life expectancy, premature mortality, and infant mortality are overarching health status indicators that reflect not only individual lifestyles and the nature of health systems but also the socio-economic conditions in various regions. In fact, many health experts see the infant mortality rate as a sentinel indicator of population health and the well-being of a society.3

The self-reported health and self-reported mental health status indicators represent physical, emotional, and social aspects of health and well-being. How people feel about their own health is seen as a good indication of the burden of disease.

The mortality rates for diseases that are leading causes of death in Canada are also benchmarked. The top three killers in Canada remain cancer, heart disease, and stroke. Cancer and heart disease alone were responsible for close to half the deaths in Canada in 2011.4 Respiratory diseases, diabetes, and nervous system diseases (including Alzheimer’s) are other leading causes of death.

Finally, the suicide rate is an indicator of both health and social conditions. Mental illness is involved in most suicide cases, especially as a consequence of depression or substance abuse.

We also calculate an overall health grade for each of the comparator regions, based on the aggregate performance on the 10 indicators for which international data are available (self-reported mental health is not included in the calculation). For more details on how the grades are calculated, please visit the Methodology page.

It is important to note that the Conference Board is not attempting to rate Canada’s health care system. Although the health care system has an impact on population health, our goal is to evaluate the health status of Canadians and of their peers in other countries.

What does the provincial health report card look like?

What does Canada’s overall report card look like?

Overall, Canada gets a “B” grade on the health report card, ranking 8th among the 16 peer countries. While Canada’s overall “B” is good, there is definitely room for improvement. Canada’s only “A”s are on the self-reported health indicators. On most indicators, Canada scores “B”s and ranks in the middle of the pack against peer countries. Canada’s worst grades are the “C”s it gets on two indicators: infant mortality and mortality due to diabetes.

Which provinces are top-ranked on health?

Generally, the four most populous provinces do best on this report card, although P.E.I. also manages to get a “B” grade overall. British Columbia and Ontario are the top-rated provinces. Not only do they rank highest within Canada, B.C. places 3rd among all the comparator regions and scores an “A” grade on the overall Health report card, while Ontario finishes with a “B” grade and ranks 7th overall. These two provinces are blessed with the best health outcomes, largely because their residents lead healthier lifestyles than those in other provinces. For instance, the shares of daily smokers and heavy drinkers are lowest in both provinces. B.C. has the highest share of the population that is physically active and the lowest obesity rate in the country. Ontario’s obesity rate is also relatively low and below the national average.5

British Columbia, the top-ranked province, places third behind Switzerland and Sweden, with “A”s on 4 of the 11 indicators. At 82.2 years, life expectancy in B.C. is among the highest in the world. B.C. also gets “A”s for premature mortality, mortality due to cancer, and self-reported health status. B.C. scores “B” grades on six indicators, including mortality due to nervous system diseases, respiratory diseases, and heart disease and stroke. The province earns its lowest grade, a “C,” on mortality due to diabetes, but it has the lowest diabetes prevalence rate in Canada. Given its low obesity rate and strong performance on other diabetes risk factors, B.C.’s relatively low ranking on diabetes mortality is puzzling and needs to be further investigated.

Ontario also finishes with four “A” grades, on life expectancy, premature mortality, self-reported mental health, and suicides. The province has the lowest suicide rate in the country, the second-lowest premature mortality rate, and the second-highest life expectancy. On self-reported health, Ontario was one of the five regions in Canada to receive an “A+” grade. Ontario earns a “B” on four indicators: mortality due to cancer, heart disease and stroke, respiratory diseases, and nervous system diseases. Like B.C., Ontario does not score any “D” grades, but earns “C”s on mortality due to diabetes and on infant mortality. Ontario’s infant mortality rate of 4.9 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2011 was worse than that of 14 of Canada’s peer countries.

The chart below is a snapshot of these provinces’ health performance relative to the top-performing peer country—represented by the red line—on the 10 health indicators for which international data are available. An index score close to the red line means the province is close to the top country on the given indicator. A score crossing the red line (above 100) means the province does better than the top-performing country. The worst-performing country is represented by a score of 0, and so a negative score means the province does worse than the poorest-performing peer country.

As shown in the chart, Ontario does better than the top-performing peer country on self-reported health status. All in all, both Ontario and B.C. perform very favourably against the top-ranked peer country on each indicator, and neither province is even close to doing worse than the poorest-performing peer countries on any of the indicators.

How do the other most populous provinces do?

Quebec and Alberta place 11th and 13th, respectively. Each scores a “B” grade overall. Like all the provinces and territories, they rank high on self-reported health status. They have mixed results overall, performing relatively well on some indicators and poorly on others.

With its 11th-place finish overall, Quebec’s best performance is an “A+” on self-reported health, placing higher than all other provinces and all the peer countries. Quebec scores “A” grades on premature mortality and mortality due to heart disease and stroke. On both these indicators, Quebec is the top-performing province, placing well above the Canadian average. The province also scores an “A” on self-reported mental health, ranking 2nd among all provinces and territories. Quebec scores “B” grades on five indicators: life expectancy, suicides, and mortality due to respiratory diseases, diabetes, and nervous system diseases. Quebec has the third-highest life expectancy in the country, after B.C. and Ontario. The province’s lowest grades are “C”s for mortality due to cancer and infant mortality. Quebec’s low ranking on cancer mortality is primarily due to lung cancer deaths—the province has the third-highest rate of lung cancer mortality in Canada.

Like Quebec, 13th-place Alberta also receives an “A+” on self-reported health. Alberta scores an “A” on mortality due to cancer and ranks just below the top-performing province, British Columbia. Alberta scores “B”s on most indicators, including life expectancy, premature mortality, and mortality due to respiratory diseases, nervous system diseases, and diabetes. Alberta gets a “C” on mortality due to heart disease and stroke and its lowest grade, a “D,” on infant mortality, ranking below the Canadian average on both indicators. Alberta has one of the highest infant mortality rates among the provinces and peer countries.

The chart below is a snapshot of these provinces’ health performance relative to the top-performing peer country—represented by the red line—on the 10 health indicators for which international data are available. An index score close to the red line means the province is close to the top country on the given indicator. A score crossing the red line (above 100) means the province does better than the top-performing country. The worst-performing country is represented by a score of 0, and so a negative score means the province does worse than the poorest-performing peer country.

How do the Maritimes do?

Although the Maritime provinces all get “A”s for self-reported health and self-reported mental health, their overall health marks are dramatically different: P.E.I. gets a “B” for its 12th-place finish, New Brunswick gets a “C” for its 17th-place finish, and Nova Scotia gets a “D” for being 22nd, just ahead of Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

P.E.I.’s “A” for the second-lowest suicide rate in the country (after Ontario) helps pull up its overall grade. P.E.I. scores “B” grades on four indicators: premature mortality, infant mortality, mortality due to diabetes, and mortality due to nervous system diseases. P.E.I. also earns four “C”s—on life expectancy and on mortality due to cancer, heart disease and stroke, and respiratory diseases. The province has no “D”s.

Although New Brunswick gets “B” grades for life expectancy and heart disease and stroke, its mortality due to diabetes and its suicide rate are worse than P.E.I.’s, contributing to its overall “C” grade for health.

Nova Scotia’s “D” on mortality due to cancer drags down its overall grade for health. Nova Scotia also ranks relatively low on life expectancy and infant mortality, earning “C” grades on both.

The chart below is a snapshot of the Maritime provinces’ health performance relative to the top-performing peer country—represented by the red line—on the 10 health indicators for which international data are available. An index score close to the red line means the province is close to the top country on the given indicator. A score crossing the red line (above 100) means the province does better than the top-performing country. The worst-performing country is represented by a score of 0, and so a negative score means the province does worse than the poorest-performing peer country.

Although P.E.I., New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia perform relatively well against the peer countries on some indicators, their performance on mortality due to cancer and respiratory diseases is weak.

Which are the worst-ranking provinces on health?

In addition to Nova Scotia, three other Canadian provinces score “D” grades on the overall health report card: Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador. These provinces also all get at least one “D–” grade. All have poor outcomes on most mortality indicators, resulting in lower life expectancies. However, each province scores high on self-reported health status, so despite the poor health outcomes, the residents of these provinces believe they are in good health. Poorer health outcomes among the Aboriginal populations may be affecting the overall performance in these provinces, all of which have a higher proportion of Aboriginal people than the Canadian average—particularly Manitoba and Saskatchewan, where over 15 per cent of the population is Aboriginal.6

Not surprisingly, residents in these three provinces rank lower on lifestyle factors than those in other provinces. The proportion of daily smokers in all three provinces is higher than the Canadian average, while the share of heavy drinkers is higher than the Canadian average in Newfoundland and Labrador and in Manitoba. Newfoundland and Labrador and Saskatchewan also have lower shares of the population that are physically active relative to the national average. Obesity rates are high in all three provinces; Newfoundland and Labrador has the highest obesity rate in the country—nearly 30 per cent of the adult population is obese.7

Newfoundland and Labrador ranks last among the provinces and 26th among the 29 comparator regions overall—only the territories fare worse. The province scores a “D–” on mortality due to diabetes, ranking lower than the worst-performing peer country and second-to-last overall. Newfoundland and Labrador scores “D”s on infant mortality and mortality due to cancer and is the bottom-ranked province on both indicators. It ranks second-lowest on mortality due to heart disease and stroke, yet manages to get a “C” grade only because last-place Finland’s mortality rate is much higher. The province earns “C” grades on two other indicators: life expectancy and mortality due to respiratory diseases. Newfoundland and Labrador earns “B” grades on premature mortality, suicides, and mortality due to nervous system disease. However, similar to its grade on heart disease and stroke, the grade on nervous system diseases largely reflects Finland’s extremely poor performance on this indicator. Newfoundland ranks 23rd among the 29 regions on mortality due to nervous system diseases—if Finland were excluded, Newfoundland and Labrador would receive a “C” on this indicator. The province earns its only “A”s for self-reported health and self-reported mental health.

Saskatchewan ranks second-to-last among the provinces, 24th overall, and like Manitoba, better than only one peer country, the United States. The province scores a “D-” on infant mortality, with an infant mortality rate higher than that of the worst-ranked peer country, the United States. Saskatchewan earns “D”s on life expectancy and premature mortality—it is the worst-performing province on both indicators. The province also scores a “D” on mortality due to diabetes. Saskatchewan earns a lone “C” on suicides, but has one of the highest suicide rates in the country—only Nunavut and N.W.T. fare worse. The province does do better on other indicators, scoring “B”s on mortality due to cancer, heart disease and stroke, respiratory diseases, and nervous system diseases as well as self-reported mental health. Saskatchewan earns its only “A” on self-reported health.

Manitoba ranks 23rd among the 29 comparator regions, finishing just ahead of Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador. It gets a “D–” on infant mortality and is the worst-performing province on this indicator. The province also does poorly on mortality due to diabetes and premature mortality, scoring “D”s on both. Manitoba earns “C”s on life expectancy and mortality due to cancer. Like Saskatchewan, Manitoba scores “B”s on mortality due to heart disease and stroke, respiratory diseases, and nervous system diseases as well as self-reported mental health. The province also gets a “B” for suicides. Manitoba earns its top grade, an “A+,” on self-reported health.

The chart below is a snapshot of these three provinces’ health performance relative to the top-performing peer country—represented by the red line—on the 10 health indicators for which international data are available. An index score close to the red line means the province is close to the top country on the given indicator. A score crossing the red line (above 100) means the province does better than the top-performing country. The worst-performing country is represented by a score of 0, and so a negative score means the province does worse than the worst-performing peer country.

All three provinces do worse than the bottom-ranked peer country on one indicator. Manitoba and Saskatchewan both rank lower than the bottom-ranked peer country on infant mortality. Manitoba ranks close to the worst-performing country on mortality due to diabetes; while Saskatchewan ranks near the bottom on premature mortality. Newfoundland and Labrador fares worse than the poorest-performing peer country on mortality due to diabetes and almost as badly as the worst-performing peer country on mortality due to cancer and infant mortality.

What about the territories?

The territories rank at the bottom of the pack overall and are the worst, or close to the worst, performers on most of the report card indicators. Poorer health outcomes among the Aboriginal populations may be affecting the overall results in these regions, especially in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, which have the highest shares of Aboriginal people.

On many risk factors (such as obesity, physical activity, and fruit and vegetable consumption), Nunavut does much worse than the Canadian average. For instance, about 48 per cent of Nunavut residents smoke daily, compared with 14 per cent for Canada as a whole. Furthermore, almost 27 per cent of adults in the territory are classified as obese. Yukon and the Northwest Territories also generally do worse than the Canadian average on risk factors for health, but the difference is not as pronounced as it is in Nunavut.8

Some of the health rankings for the territories appear contradictory. For instance, each territory scores a “D-” on life expectancy but earns an “A” or “A+” on self-reported health. Nunavut’s results seem puzzling at first—the territory, which ranks last overall, receives at least an “A” on four indicators, one “D,” and a “D-” on the remaining six indicators, namely life expectancy, premature mortality, infant mortality, suicides, mortality due to cancer, and mortality due to respiratory diseases. Nunavut’s “D” on self-reported mental health is not surprising given its phenomenally high suicide rate. On the flip side, Nunavut scores an “A+” on mortality due to diabetes and “A”s on mortality due to nervous system diseases and heart disease and stroke. Death from these diseases mainly occurs later in life. Given the low life expectancy and high premature mortality rate in Nunavut, its “A”s on these indicators likely reflect the fact that the majority of the population does not live long enough to suffer from diseases that arise later in life. Nunavut’s life expectancy at birth is only 71.8 years—much lower than the national average of 81.5 years.

The Northwest Territories receives a “D-” on four indicators, ranking worse than the poorest-performing peer country on life expectancy, premature mortality, infant mortality, and mortality due to cancer. The territory also does poorly on mortality due to respiratory diseases, ranking third from the bottom and scoring a “D.” On the indicators where N.W.T. earns a “C”—suicides and mortality due to heart disease and stroke—the territory still finishes in the bottom quarter of the rankings. N.W.T.’s best performance is on self-reported health, where it scores an “A+” and is the top-ranked overall. Like Nunavut, N.W.T. also earns high grades on mortality due to nervous system diseases and diabetes, earning “A”s on both indicators. As is the case in Nunavut, the strong performance on these two indicators likely reflects the fact that deaths from these diseases typically occur later in life—and in a region like N.W.T., which has a low life expectancy and high premature mortality rate, people are dying prematurely of other diseases.

Yukon sits third from the bottom overall and has more balanced rankings on the health indicators than the other two territories. The territory earns fewer “A”s than N.W.T. and Nunavut, but it also earns fewer “D-”s. Similar to the other provinces and territories, Yukon receives an “A” on self-reported health, but also scores an “A” for having one of the lowest suicide rates in the country. Yukon’s scores “B”s on mortality due to heart disease and stroke, mortality due to nervous system diseases, and self-reported mental health. Yukon earns “D-” grades on life expectancy and on mortality due to cancer and diabetes and “C”s on premature mortality and infant mortality.

The chart below is a snapshot of the territories’ health performance relative to the top-performing peer country—represented by the red line—on the 10 health indicators for which international data are available. An index score close to the red line means the territory is close to the top country on the given indicator. A score crossing the red line (above 100) means the territory does better than the top-performing country. The worst-performing country is represented by a score of 0, and so a negative score means the territory does worse than the poorest-performing peer country.

As shown in the chart, the territories do worse than the bottom-performing peer country on several indicators. In fact, Nunavut ranks below the worst-performing peer country on six of the ten indicator indicators, while N.W.T. does worse on four indicators and Yukon on three. All three territories rank as well as or better than the best performing country on self-reported health, while Nunavut fares better than the top-ranking country on mortality due to diabetes.

Are Canadians gambling with their health?

Assessing a region’s performance on the risk factors that lead to chronic diseases such as heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and respiratory system diseases is as important as assessing its approach to and success with treatment. Although Canada ranks well among comparator countries when it comes to some risk factors (such as alcohol and tobacco consumption), there are definitely areas where improvements can be made. In particular, obesity is one of the most significant contributing factors to many chronic conditions, including heart disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes—type 2 diabetes accounts for 85 to 95 per cent of all diabetes cases in high-income countries. The share of overweight or obese Canadians continues to increase, with the highest rates of obesity in the Atlantic provinces. In each of these four provinces, more than a quarter of the adult population were considered to obese in 2013, well above the Canadian average of 18.2 per cent. Nunavut and N.W.T. also have high obesity rates. Particularly troubling is the growing share of children who are overweight or obese. Although the rates of childhood obesity are highest in the Atlantic provinces, nearly all provinces and territories have experienced an increase in childhood obesity in the last decade. The rising obesity rates for Canadians of all ages clearly places them at risk for future chronic diseases.

Smoking is a risk factor that has gone down in Canada. True, the high number of deaths from lung cancer reflects the smoking habits of Canadians in previous decades, but since then campaigns to curtail smoking and anti-smoking bans in public places throughout the country have helped Canada to register one of the lowest proportions of smokers among all countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Over the last decade, smoking rates have come down in all provinces and territories, and so have the number of new lung cancer cases. Similarly, new cases of respiratory diseases like COPD have also been trending downward over the last decade (except in Newfoundland and Labrador and Alberta). The declining smoking rates augur well for the future risk of lung diseases.

Lifestyle choices, such as physical activity and diet, affect health outcomes. Estimates suggest that one-third of cancers could be prevented with increased vegetable and fruit consumption, increased physical activity, and maintenance of a healthy body weight. Some of the strongest evidence of the relationship between diet and cancer has found that diets high in vegetables and fruit provide protection against cancer.9

But many Canadians have yet to act on this evidence. According to the latest data from the Canadian Community Health Survey, only 40.8 per cent of Canadians said they consumed fruit and vegetables five or more times per day in 2013—down from 45.6 per cent in 2009.10 What is more troubling is that only Quebec and Alberta had fruit and vegetable consumption above the Canadian average in 2013—7 out of 10 provinces and all three territories had less than 40 per cent of residents consuming fruit and vegetables five or more times per day.

Physical activity numbers are better—56.3 per cent of Canadians were at least moderately active during their leisure time in 2013.11 Moderately active is equivalent to walking at least 30 minutes a day or taking an hour-long exercise class at least three times a week.12 The good news is that the trend for moderate exercise has been rising in almost all provinces and territories over the past decade. With obesity rates on the rise in all provinces, improvements can be made by Canadians to both diet and physical activity to limit the risk factors of disease.

Results suggest that even a modest improvement in physical activity can yield tangible benefits. Indeed, by simply getting 10 per cent of Canadians with suboptimal levels of physical activity to reduce their sedentary behaviour and exercise more, the incidence rates for major chronic conditions like heart disease, cancer, hypertension, and diabetes would be reduced substantially. This would boost life expectancy and lessen the burden on the health care system.13

What can be done to boost health outcomes in the territories?

The territories have small populations living in vast geographic areas. This coupled with poor infrastructure means that health care is not easily accessible for most. Poor socio-economic conditions in the territories—particularly among the Aboriginal populations—have affected health outcomes. Efforts must be made to improve socio-economic factors that have a huge impact on the health of the population—like poverty, income inequality, cost of living, infrastructure, recreation, housing, and education.

Socio-economic status also plays a role in health outcomes by affecting lifestyle choices. The prevalence of lifestyle-related risk factors is often higher for socio-economically disadvantaged groups. The territories, particularly Nunavut, fare poorly on many lifestyle-related risk factors. Obesity rates and smoking rates are well above the Canadian average in all three territories, while fruit and vegetable consumption is significantly below the Canadian average. This is partially explained by the high cost of high-quality food in the territories compared with the Canadian average. For example, according to the Nunavut Bureau of Statistics, in 2014, the average Canadian price for one kilogram of apples was under $4, while the average price in Nunavut was $7. Difficulties in accessing affordable fruits and vegetables places the residents of the territories at a higher risk of developing a chronic disease. Indeed, incidence rates for diabetes have been rising in the territories over the last decade.

To boost health outcomes in the territories, a tailored approach may be required. Many Northern Aboriginal populations have a strong sense of community, with cultural traditions that foster respect for the wisdom of elders and one’s interconnectedness with land and nature. Therefore, health policy must be inclusive of Aboriginal traditional knowledge, building on strengths that reinforce the sense of community. This should include programs that help Aboriginal youth find purpose, build self-esteem, and assume leadership responsibilities for their families and communities.

As well, efforts must continue to develop culturally appropriate measurement tools and indicators to evaluate health and wellness programs, ensuring that quality research documents the successes and shortcomings of programs and initiatives in different regions. Integrating public and private funding opportunities with community-driven programs and projects can help to pull together limited financial and human resources in the North.14

What will it take for Canada to be a top performer?

Funding for health promotion and disease prevention invariably competes with the financial demands of the health care system. It is often politically difficult to deny urgent needs in the present to invest in the future.

Yet the demographic profile of Canadian society is changing as the population ages, affecting the incidence of chronic disease. By 2036, the proportion of Canadians over 65 will be 26 per cent—nearly double what it was in 2009.15 It will be even worse in the Atlantic provinces, where the share over 65 is expected to be about 33 per cent.16 These provinces also face the greatest risk of developing chronic diseases due to poor lifestyle choices. Canada is already facing a growing burden from chronic diseases—health care costs continue to rise, with chronic care consuming an ever-larger share of total health care spending. This will become even worse as the population ages because Canada is not making enough progress in disease prevention and health promotion.

More health spending does not necessarily translate into better health outcomes, however. Given the rising rates of chronic diseases and the impact that lifestyle choices have on these diseases, active participation of patients in setting their own health goals and management plans is more relevant than ever before. Greater emphasis on evidence-based approaches, greater use of collaborative interprofessional care, and increased self-management hold great promise for Canada’s health care system in the future. For example, the proportion of British Columbia’s population over 65 (16.4 per cent) is not much lower than the Atlantic provinces’ (17.5 per cent), yet thanks in large part to their lifestyle choices, B.C. residents continue to have much better health outcomes.17

Canada has no choice but to adopt a model that focuses on sound primary care practices and population health approaches—particularly preventing and managing chronic diseases—and recognizes and rewards high-quality health care services. Targets set by governments in the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Integrated Pan-Canadian Healthy Living Strategy are the building blocks of a prevention-oriented strategy. B.C.’s internationally lauded ActNow program, which encourages citizens to exercise more and eat healthier food, is a promising model of intra-governmental collaboration to develop health policy. Healthy Change, Ontario’s action plan for health care, seeks to not only improve patient care but also help residents make healthier choices. Developing a report card that assesses Canada’s progress on its health care goals would be an important component of a new business model for health care.

Population health strategies must target funding for improved information technology, electronic patient records, training and development, and innovation that will allow Canada to renew its health care system and make it among the best. Greater receptivity to innovative technologies and delivery systems—together with supportive environments and policies to speed of their adoption—is essential to implement new approaches to wellness and disease prevention and management that will optimize Canada’s health care resources and improve population health outcomes.

Footnotes

1 World Health Organization, Constitution of the World Health Organization (accessed September 13, 2009).

2 For more details on how the grades are calculated, please visit the Methodology page.

3 United Nations, Human Development Report 2005 (New York: UNDP, 2005), 4.

4 Statistics Canada, “Ranking, Number, and Percentage of Deaths for the 10 Leading Causes, Canada, 2000, 2010 and 2011,” Causes of Death, 2010 and 2011 (accessed December 2, 2014).

5 Statistics Canada, CANSIM table 105-0501, Health Indicator Profile, Annual Estimates, by Age Group and Sex, Canada, Provinces, Territories, Health Regions (2013 Boundaries) and Peer Groups (accessed December 2, 2014).

6 Statistics Canada, National Household Survey, Number and Distribution of the Population Reporting an Aboriginal Identity and Percentage of Aboriginal People in the Population, Canada, Provinces and Territories, 2011 (accessed December 2, 2014).

7 Statistics Canada, CANSIM table 105-0503, Health Indicator Profile, Age-Standardized Rate, Annual Estimates, by Sex, Canada, Provinces and Territories (accessed December 2, 2014).

8 Ibid.

9 Cancer Care Ontario, Insight on Cancer: News and Information on Nutrition and Cancer Prevention, Volume Two, Supplement One: Vegetable and Fruit Intake (Toronto: Cancer Care Ontario, 2005), 6.

10 Statistics Canada, CANSIM table 105-0503, Health Indicator Profile, Age-Standardized Rate, Annual Estimates, by Sex, Canada, Provinces and Territories (accessed December 2, 2014).

11 Ibid.

12 Statistics Canada, Physical Activity During Leisure Time, 2010 (accessed February 14, 2012).

13 Fares Bounajm, Thy Dinh, and Louis Thériault, Moving Ahead: The Economic Impact of Reducing Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behaviour (Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2014).

14 Siomonn Pulla, Building on Our Strengths: Aboriginal Youth Wellness in Canada’s North (Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2013).

15 Statistics Canada, population projection, custom tabulation.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.