Health

Key Messages

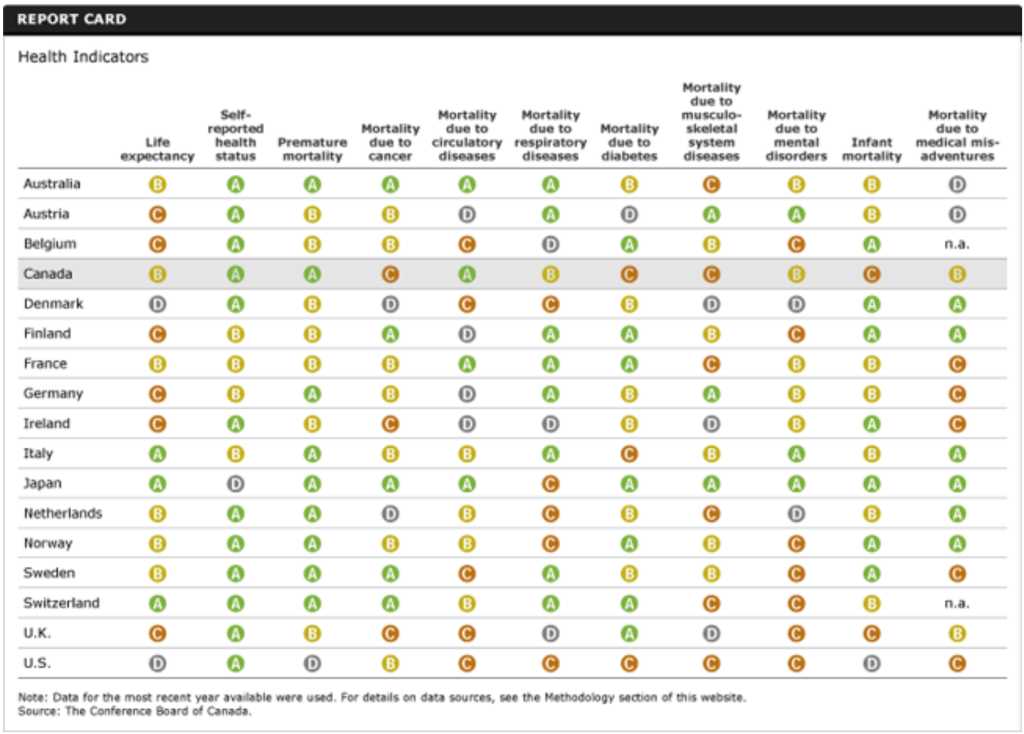

- Canada maintains its “B” grade and 10th-place ranking among the 17 peer countries.

- As the population ages, chronic diseases will place an increasing burden on Canadian society.

- Obesity is one of the most significant contributing factors to many chronic conditions, including heart disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes.

Indicators

Putting Health in context

What is health? For some, health means the absence of disease and pain; for others, it is a general feeling of wellness. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health more broadly: “the state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”1

This broad definition aligns with the Conference Board’s overarching goal in benchmarking Canada’s performance—to measure quality of life in Canada and in its peer countries. Most Canadians would agree that without health, quality of life is severely compromised.

How do we measure health performance?

To measure health performance, we evaluate Canada and 16 peer countries on the following 11 report card indicators: life expectancy; self-reported health status; premature mortality; mortality due to cancer; mortality due to circulatory disease; mortality due to respiratory disease; mortality due to diabetes; mortality due to diseases of the musculoskeletal system; mortality due to mental disorders; infant mortality; and mortality due to medical misadventures.

It is important to note that the Conference Board is not attempting to rate Canada’s health care system. Although the health care system has an impact on the health status of a population, our goal is to evaluate the health status of Canadians and of their peers in other countries.

How does Canada score?

Canada gets a “B” for its overall health performance.

On the surface, this puts Canada in good standing, but the results also reveal a disturbing fact showing that relative to its peer countries, Canada’s performance is weak on key indicators. Although Canada has no “D” grades, its “C”s for mortality due to cancer, mortality due to diabetes, mortality due to musculoskeletal diseases, and infant mortality point to areas that require focus to improve the overall health of Canadians and to increase Canada’s standing in relation to its peers.

Diabetes remains a growing concern. Canada has the third highest mortality rate due to diabetes among the peer countries, and diabetes prevalence continues to increase. This should be raising alarm bells, not only among Canadian policy-makers but also among the public.

Canada scores “A” grades on three indicators: self-reported health status, premature mortality, and mortality due to circulatory diseases. Canada achieves “B” grades for life expectancy, mortality due to respiratory diseases, mortality due to mental disorders, and mortality due to medical misadventures.

Why does Canada get a “B” when its health care system is one of the best in the world?

Canada’s middle-of-the-road ranking overall—a solid “B”—would surprise most Canadians who are immensely proud of their health care system. Canadians have universal access to health care services, highly skilled and committed health care professionals, and internationally recognized health care and research institutions. But the Canadian health care system also has challenges. These include limited availability of comprehensive health information systems, wait times for some health care diagnostics and treatments, and management systems that don’t focus enough on the quality of health outcomes.

What’s more, health care is just one of several contributors to the health of Canadians; other factors also come into play, such as the age of the population and lifestyle choices including tobacco use, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and eating habits. These factors are, for the most part, independent of the formal health care system.

Lifestyle choices are integral to determining the degree to which a population may suffer from chronic disease. In 2005, for example, the World Health Organization estimated that Canada would lose US$500 million in national income from premature deaths due to heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.2 As more people die each year, these losses accumulate; financial losses due to these premature deaths will skyrocket to an estimated US$1.5 billion by 2015, triple the 2005 numbers. If Canadians adjust their lifestyles to reduce risks, however, these morbidity and mortality rates—and their associated costs—can be reduced.

Are Canadians healthier today than in the past?

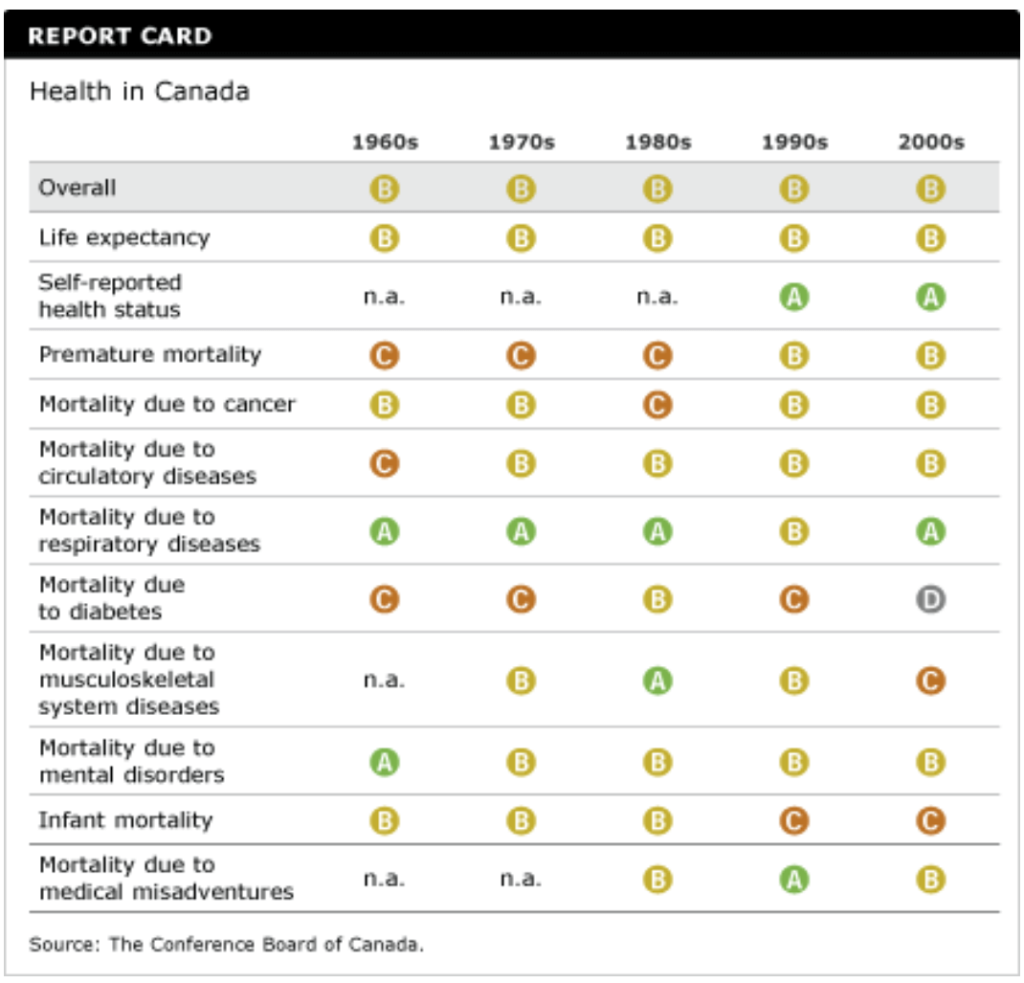

The radar diagram below provides a snapshot of Canada’s health performance on the 11 indicators relative to the best-performing country for each decade. It has 11 axes—one for each indicator—that radiate out from the centre. A score closer to the centre represents worse performance, while a score closer to the outer circle represents better performance.

On balance, fewer Canadians are dying today from the diseases benchmarked here than they did in the 1960s and 1970s. Clearly, progress is being made in reducing the number of people dying from catastrophic disease.

Relative to its peers, however, Canada has dropped to 10th place from a much more enviable 5th place in the 1990s.

Canada’s relative performance has fallen on several indicators—specifically, mortality due to medical misadventures, mental disorders, diabetes, musculoskeletal system diseases, and cancer.

The mortality rate due to misadventures during medical care is higher now than it was in the early 1980s, and so Canada’s relative ranking on this indicator dropped from an “A” in the 1990s to a “B” in the 2000s. However, this increase might be due to increased reporting of misadventures, resulting from greater awareness of the importance of reporting and the availability of better tracking systems that have been generated by recent patient safety movements.

Canada’s high mortality rate due to mental disorders is a concern. Mental illness not only affects personal relationships and physical health, it can also have a huge impact on workplace performance. Depression has been linked to absenteeism and reduced productivity in the workplace. The federal government established the Mental Health Commission in August 2007 to address mental health issues in the country. The Commission launched an initiative to reduce the stigma on mental illness in 2009 and released a framework for a mental health strategy to transform mental health systems in Canada.

Diabetes continues to be a serious concern. An estimated 2 million Canadians have been diagnosed with diabetes, and the number suffering from this chronic condition is likely much greater given that it often remains undiagnosed for years. Among the peer countries, Canada has the second-highest prevalence of diabetes. Even more distressing is the fact that the prevalence of diabetes continues to increase, for both men and women.

Canada’s grade on mortality due to musculoskeletal system diseases slipped from an “A” in the 1980s to a “C” in the 2000s. Canada now ranks 11th among the 17 peer countries on this indicator. Musculoskeletal disorders will have a greater impact on Canadians in the future given that the population is aging and older people are more affected by conditions such as arthritis and osteoporosis.

Although cancer mortality rates have fallen, cancer will continue to place an increasing burden on Canadian society. The number of new cancer cases is rising as the Canadian population grows and ages. Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death for both men and women in Canada. The most prevalent form of cancer among men is prostate cancer, and, for women, breast cancer incidence is nearly double lung cancer incidence.

Are Canadians gambling with their health?

Assessing Canada’s performance on the risk factors that lead to heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and respiratory disease is as important as assessing its approach to and success with treatment. Canada is a top performer among comparator countries on two leading risk factors: tobacco and alcohol consumption. The high number of deaths from lung cancer reflects the smoking habits of Canadians in previous decades; since then, campaigns to curtail smoking and anti-smoking bans in public places throughout the country have helped Canada to register one of the lowest proportion of smokers among all OECD countries. This augurs well for the future risk of lung diseases.

At the time of the 1974 Lalonde Report on health, Canada was looked to as a world leader in the area of public health, including disease prevention and health promotion. Canada’s proud record in turning around tobacco consumption demonstrated the ability to create behavioural change in society. Canada will need to rally the same resources to overcome similar risks, such as obesity.

Obesity has taken centre stage as a major risk factor for chronic diseases. Obesity is one of the most significant contributing factors to many chronic conditions, including heart disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes—type 2 diabetes accounts for 85 to 95 per cent of all diabetes cases in high-income countries. The share of overweight or obese Canadians continues to increase. According to calculations based on measured data, almost two-thirds of Canadians were considered to be either overweight or obese in 2008, and 24 per cent were considered to be obese. Particularly troubling is the growing share of children who are overweight. More than one in four Canadian children are considered overweight—a share that is higher than the OECD average.

Lifestyle choices, such as physical activity and diet, affect health outcomes. Estimates suggest that one-third of cancers could be prevented with increased vegetable and fruit consumption, increased physical activity, and maintenance of a healthy body weight. Some of the strongest evidence of the relationship between diet and cancer has found that diets high in vegetables and fruit provide protection against cancer.3

But many Canadians have yet to act on this evidence. In 2000, Health Canada, Statistics Canada, and the Canadian Institute for Health Information started the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) to collect population-level information on health determinants, health status, and health system use. CCHS tracks variables including physical activity and diet. According to the latest CCHS data, in 2010, only 43 per cent of Canadians said they consumed fruit and vegetables five or more times per day—down from 45.6 per cent in 2009.4 Similar data for physical activity indicate that, in 2010, 52 per cent of Canadians were at least moderately active during their leisure time. Moderately active is equivalent to walking at least 30 minutes a day or taking an hour-long exercise class at least three times a week.5

How does Canada compare to the class average?

The radar diagram below provides a snapshot of Canada’s health performance on the 11 indicators relative to the best-performing country and the 17-country average. (For the mortality rate due to medical misadventures, it’s a 15-country average that excludes Belgium and Switzerland because equivalent data were not available.) The diagram has 11 axes—one for each indicator—that radiate out from the centre. A score closer to the centre represents worse performance, while a score closer to the outer ring represents better performance.

Canada performs better than the peer-country average on seven indicators: life expectancy, self-reported health status, premature mortality, mortality due to circulatory diseases, mortality due to respiratory diseases, mortality due to mental disorders, and mortality due to medical misadventures. Canada’s performance is noticeably worse than the peer-country average on four indicators: mortality due to cancer, mortality due to diabetes, mortality due to diseases of the musculoskeletal system, and infant mortality.

Who’s at the top of the class?

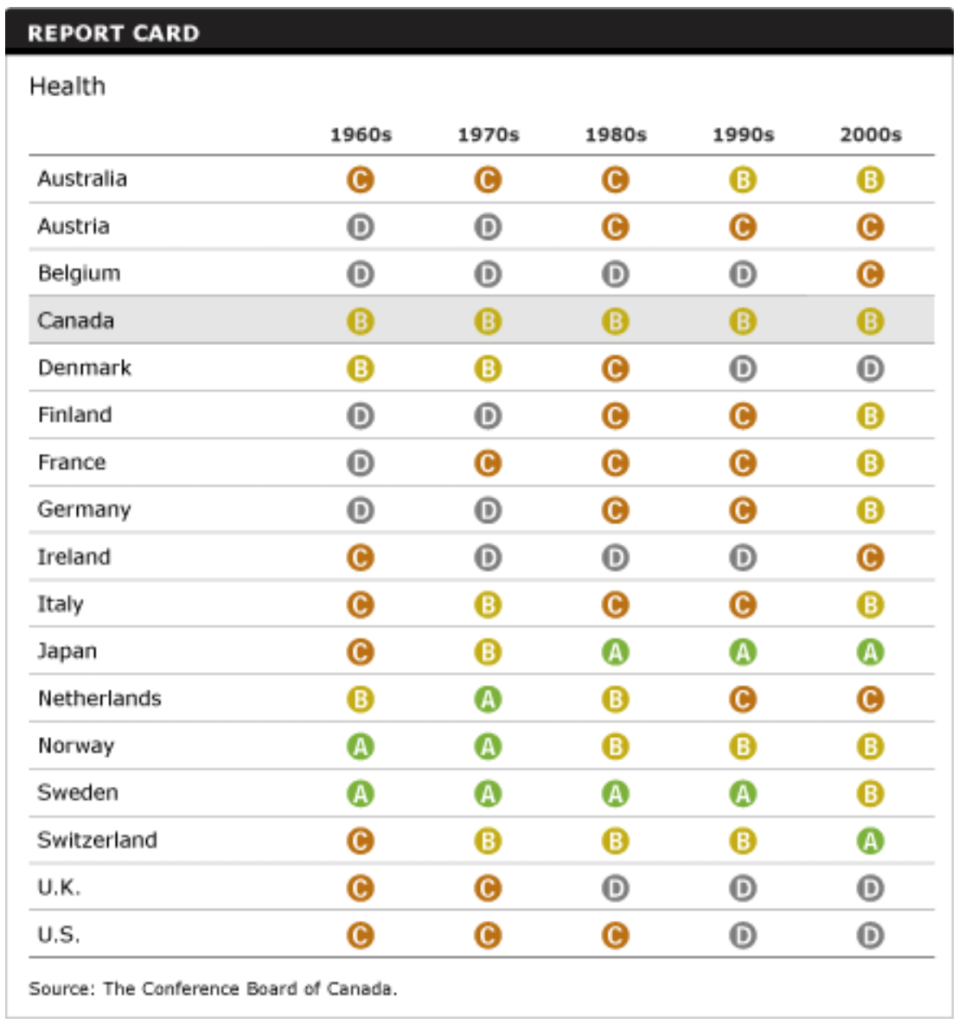

Japan—a “C” performer in the 1960s—has made great strides in the overall health of its population and has been a consistent “A” performer since the 1970s. Japan and Switzerland were the only “A” performers in the 2000s. Eight countries received “B”s for the 2000s.

There is no easy, single answer to the question of why other countries are doing better than Canada. Most top-performing countries have achieved better health outcomes through actions on the broader determinants of health such as environmental stewardship and health-promotion programs focusing on changes in lifestyle, including smoking cessation, increased activity, healthier diets, and safer driving habits. Leading countries also focus on other determinants of health—such as education, early childhood development, income, and social status—to improve health outcomes.

What will it take for Canada to be a top performer?

Funding for health promotion and disease prevention invariably competes with the financial demands of the health care system. It is often politically difficult to deny urgent needs in the present to invest in the future.

Yet the demographic profile of Canadian society is changing as the population ages, affecting the incidence of chronic disease. By 2036, the proportion of Canadians over 65 will be between 23 and 25 per cent—nearly double what it was in 2009.6 The country is already facing a growing burden from chronic diseases. Health care costs continue to rise, with chronic care consuming an ever-larger share of total health care spending. Canada is not making significant progress in prevention and health promotion.

Countries with considerably older populations than Canada’s—like Japan and Sweden—do not have more expensive health systems. More health spending does not necessarily translate into better health outcomes. In fact, Japan, which has the lowest health care spending per capita, boasts the highest life expectancy and the lowest infant mortality rate. Japan also has one of the lowest premature mortality rates, the second-lowest mortality rate due to cancer, and the lowest rates of mortality due to circulatory diseases, diabetes, and mental illness.

Sweden, another country with one of the oldest populations is the world, scores “A” grades on five of the health indicators. Sweden has prioritized an integrated approach, tailoring home care, health care, and fitness activities to the needs of older Swedes.

Given the rising rates of chronic diseases and the impact that lifestyle choices have on these diseases, active participation of patients in setting their own health goals and management plans is more relevant than ever before. Greater emphasis on evidence-based approaches, greater use of collaborative interprofessional care, and increased self-management hold great promise for Canada’s health care system in the future.

Canada has no choice but to adopt a model that focuses on sound primary care practices and population health approaches—particularly preventing and managing chronic diseases—and recognizes and rewards high-quality health care services. Targets set by governments in the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Integrated Pan-Canadian Healthy Living Strategy are the building blocks of a prevention-oriented strategy. British Columbia’s internationally lauded ActNow program, which encourages citizens to exercise more and eat healthier food, is a particularly promising model of intra-governmental collaboration to develop health policy. Developing a report card that assesses Canada’s progress on its health care goals would be an important component of a new business model for health care.

Population health strategies must target funding for improved information technology, electronic patient records, training and development, and innovation that will allow Canada to renew its health care system and make it among the best. Greater receptivity to innovative technologies and delivery systems—together with supportive environments and policies to speed of their adoption—is essential to implement new approaches to wellness and disease prevention and management that will optimize Canada’s health care resources and improve population health outcomes.

Interested in learning more about technological innovation in Canada’s health system?

Exploring Technological Innovation in Health Systems, Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2007.

Footnotes

1 World Health Organization, Constitution of the World Health Organization (accessed September 13, 2009).

2 World Health Organization, Preventing Chronic Diseases: A Vital Investment (Geneva: WHO, 2005), 78.

3 Cancer Care Ontario, Insight on Cancer: News and Information on Nutrition and Cancer Prevention, Volume Two, Supplement One: Vegetable and Fruit Intake (Toronto: Cancer Care Ontario, 2005), 6.

4 Statistics Canada, “Fruit and vegetable consumption, 2010” (accessed February 14, 2012).

5 Statistics Canada, “Physical activity during leisure time, 2010” (accessed February 14, 2012).

6 Statistics Canada, “Population projections: Canada, the Provinces and Territories” (accessed February 14, 2012).