Mortality Due to Diabetes

Key Messages

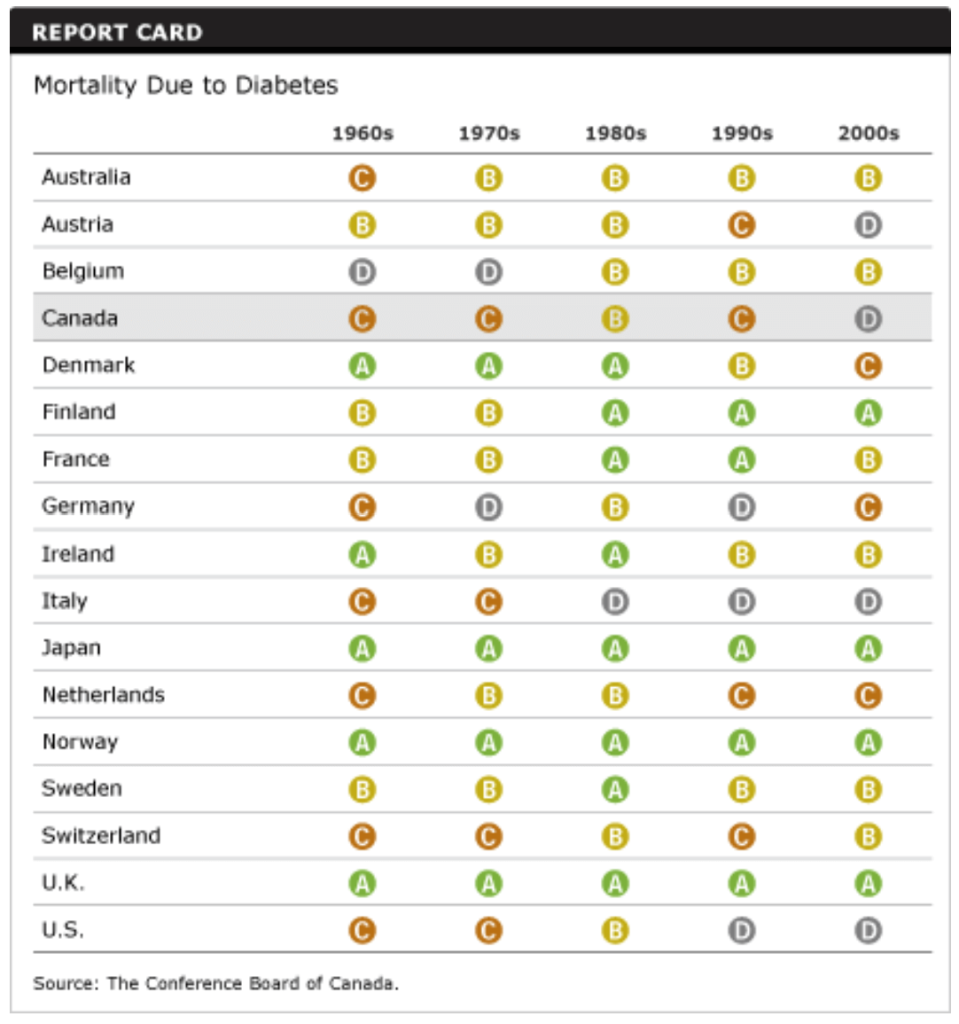

- Canada receives a “C” and ranks 15th out of 17 peer countries on mortality due to diabetes.

- Two million Canadians suffer from diabetes, a figure that is expected to increase to three million over the next decade.

- The prevalence of diabetes in Canada continues to increase.

Putting mortality due to diabetes in context

Diabetes is a global epidemic and, according to the International Diabetes Federation, “one of the most challenging health problems in the 21st century.” In 2011, diabetes accounted for about 4.6 million deaths worldwide.1

Globally, it is estimated that more than 350 million people suffer from diabetes; this number is expected to jump to over 550 million by 2030, if nothing is done.2 An estimated 280 million people worldwide have an impaired glucose tolerance—a precursor to diabetes. This number is projected to reach 398 million by 2030, or 7 per cent of the adult population.3

Diabetes has also shifted down a generation—from a disease of the elderly to one that affects those of working age or younger. According to the International Diabetes Federation, as a result of decreasing levels of physical activity and increasing obesity rates, type 2 diabetes in children has the potential to become a global public health issue.4

What is diabetes?

Diabetes is a chronic, often debilitating, and sometimes fatal disease that occurs when there are problems with the production and use of insulin in the body, ultimately leading to high blood sugar levels. Long-term complications from diabetes include kidney disease, diminishing sight, loss of feeling in the limbs, and cardiovascular disease.

There are three types of diabetes:

- Type 1 is sometimes called “insulin dependent” and is considered to be an autoimmune reaction that attacks the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas.

- Type 2 diabetes is referred to as “non-insulin dependent” or “adult onset.” It is usually controlled through diet, regular exercise, oral medication, and sometimes insulin injections.

- Gestational diabetes develops during pregnancy and usually goes away after.

How does the Canadian mortality rate due to diabetes compare to those of its peers?

Canada has the third-highest rate of mortality due to diabetes among its peer countries, giving it a “C” rating. The most recent year of published data on mortality due to diabetes for Canada is 2004, with 18 deaths per 100,000 population. That dropped to an estimated 16 deaths per 100,000 population in 2006.5 Austria is the worst performer, at 26 deaths per 100,000 population.

These high mortality rates throw a spotlight on Japan, which has a very low rate of 5.5 deaths per 100,000 population.

Has Canada improved its relative grade?

Canada earned “C”s in the 1960s and 1970s. By contrast, Denmark, Japan, Norway, and the U.K. were “A” performers then.

In the 1980s, Canada’s ranking improved to a “B,” but Finland, France, Ireland, and Sweden surpassed Canada’s improvements and joined the roster of “A” performers.

Canada’s grade slipped to a “C” in the 1990s and a “D” in the most recent decade, although it has since edged back up to a “C” in 2006. Austria, the U.S., and Italy have also been pushed to the back of this class on this indicator.

Three countries have had solid “A”s throughout the five decades: Japan, Norway, and the United Kingdom.

Are more Canadians dying of diabetes than in the past?

In the early 1980s, deaths from diabetes started to rise. The higher mortality rate was linked to an overall increase in obesity and new cases of diabetes, primarily among men.6

But in recent years, the mortality rate due to diabetes has fallen. This is likely due to better and earlier treatment of the disease, given that the prevalence of diabetes continues to increase.

Why is diabetes a concern in Canada?

Diabetes is one of the most common conditions affecting Canadians: an estimated 2 million Canadians, or 1 in 16 people, have been diagnosed with diabetes.7 The number of Canadians actually suffering from diabetes could be much greater given that many living with this chronic condition remain undiagnosed for years.

Also distressing is the fact that the prevalence of diabetes continues to increase. Between 2000–01 and 2006–07, the prevalence of diagnosed diabetes in Canada, taking into account changes in the age of the population, increased by 37 per cent.8 Diabetes prevalence is increasing for both men and women in Canada.

In 2010, Canada had the second-highest prevalence of diabetes among the peer countries.9

Diabetes has a huge economic impact. A person with diabetes can face medication and supply costs in the range of $1,000 to $15,000 a year. Diabetes-related costs—such as lab tests, physician services, and kidney analysis—amount to $15.6 billion every year in Canada, a figure that is expected to reach $19.2 billion by 2020.10 In 2010, diabetes-related health spending in OECD countries was an estimated US$345 billion.11

What accounts for rising incidences of diabetes and mortality rates?

About 85 to 95 per cent of all diabetes cases in high-income countries are type 2.12 The number of people with type 2 diabetes is increasing dramatically because of Canada’s aging population, rising obesity rates, increasingly sedentary lifestyles, and higher risk for diabetes for Aboriginal people and new Canadians.13

Physical activity, healthy eating, weight loss, not smoking, and stress reduction may help delay or prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes. One study showed that people at risk of type 2 diabetes were able to reduce their risk by 58 per cent by exercising moderately for 30 minutes a day and by losing 5–7 per cent of their body weight.14

The Canadian Community Health Survey has found links between being overweight and having concurrent high blood pressure, diabetes, and heart disease.15 Technological and treatment advances have improved Canada’s performance on heart disease, dropping the rate from 231.8 deaths per 100,000 population in 1980 to 88.4 in 2004.16 However, the rising incidence of diabetes in Canada also portends a rise in the number of deaths from heart disease as the population ages and becomes more obese and sedentary. According to the Canadian Diabetes Association, 80 per cent of people with diabetes will die as a result of heart disease or stroke, and diabetes is a contributing factor in the death of about 41,500 Canadians each year.17 In fact, Canadian adults with diabetes have mortality rates that are twice as high as the rates for adults without diabetes.18

Other factors also come into play. Aboriginal people, for example, are three to five times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes than the general population.19 People of Hispanic, Asian, South Asian, and African descent are also at a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes than people of European descent—and people from these populations make up the majority of new Canadian immigrants, the main source of Canada’s population growth. Furthermore, people from these ethnic populations who develop diabetes do so at an earlier age and at a lower body mass index (BMI).20

One of the most disturbing indicators is the growing incidence of type 2 diabetes among children from these high-risk populations. When combined with rising child obesity rates, the warning signs indicate this may be the first generation of children in more than a hundred years who can expect worse health outcomes than their parents.

Are Canadians making the wrong lifestyle choices?

Yes. The increase in type 2 diabetes is due to behavioural and lifestyle choices. Lifestyle choices, such as physical activity and diet, affect health outcomes. Obesity is one of the most significant contributing factors to many chronic conditions, including heart disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes.

The percentage of Canadians who are overweight or obese continues to increase. In 2009, 48 per cent of Canadians were overweight or obese, with a body mass index (BMI) of 25 or more. The percentage of obese Canadians, with a BMI of 30 or more, grew from 12 per cent in 1994 to 16.5 per cent in 2009.21 Furthermore, these estimates are based on self-reported height and weight. BMI estimates derived from actual measurements of height and weight paint a bleaker picture.22 According to calculations based on measured data, in 2008, 60 per cent of Canadians were considered to be either overweight or obese and 24 per cent were considered to be obese.23

Particularly troubling is the growing share of Canadian children and adolescents who are overweight, given that “excess weight in adolescence often persists into adulthood.”24 According to a recent OECD report, more than one in four Canadian children is considered overweight—a share that is higher than the OECD average and those in most of the peer countries.25 The increase in overweight children helps explain the rise in the incidence of children developing diabetes. While diet plays a big role, the likelihood of children being overweight or obese also increases as they spend more “screen time” in front of televisions, video games, or computers and lead less active lifestyles.

What can Canada do to address the dramatic rise in diabetes?

Interprofessional health care teams and case management can improve the quality of care for chronic diseases like diabetes and heart disease. Information technology can support these interprofessional health care teams by giving health care system managers and policy-makers tools such as registries for chronic diseases. And yet, although 90 per cent of family physicians in nine European countries and Australia use computers for at least some element of caring for patients, according to a recent study, only 20 per cent of Canadian family physicians used computers.26 The most common use is managing patient drug prescriptions, followed by receiving laboratory results online.

Type 2 diabetes is a complex disease with a high burden of complications. Physicians have difficulty managing diabetes as part of their daily practice. According to a 2003 study from the Diabetes in Canada Evaluation (DICE), one in two Canadians with type 2 diabetes do not have their blood sugar under control, and the longer patients have diabetes, the less likely they are to control their blood sugar.

The use of effective drugs for diabetic care is low also in Canada. The DICE study cited “clinical inertia” as the reason why knowledge is not being translated into more aggressive treatment plans.27

Only half of the family physicians in Canada say their practices are well prepared to handle patients with multiple chronic health conditions. In its report Why Health Care Renewal Matters: Lessons From Diabetes, the Health Council of Canada states that less than one-half of Canadians with diabetes get all the lab tests and procedures that experts recommend to monitor blood sugar levels, blood pressure, cholesterol, kidney health, vision, and foot health. Yet research suggests that when people with diabetes receive higher levels of preventive care, their health is better than when they do not.28

The Council points out that seeing a family physician does not always indicate a higher level of care. It found that only half of general practitioners refer their patients for more active support such as nutrition or fitness counselling.

A landmark U.K. diabetes study showed that a combination of intensive blood sugar control and oral medications was more effective than the typical approach, where doctors first try dietary and weight control measures before going on to medication.29 Consequently, the Canadian Diabetes Association’s 2003 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada now call for a more aggressive treatment approach. The DICE study showed that although family physicians are knowledgeable about these guidelines, they still rely on lifestyle modifications rather than early blood sugar control and oral medication.

Aggressive treatment is required for those with diabetes, but there must also be a focus on preventative measures. Maintaining a healthy weight through an active lifestyle and healthy eating habits reduces the risks of developing diabetes, as well as many other chronic diseases. These healthy behaviours need to be encouraged in the workplace, schools, and the community as a whole. Ultimately, of course, it is up to individuals to take responsibility for their own health and the health of their children. Individuals must be engaged when it comes to treatment—patient engagement in their own care is key to better outcomes.

Footnotes

1 International Diabetes Federation, Diabetes Atlas, Fifth Edition (accessed November 16, 2011).

2 Ibid.

3 International Diabetes Federation, Diabetes Atlas, Fifth Edition, Impaired Glucose Intolerance (accessed November 16, 2011).

4 International Diabetes Federation, Diabetes Atlas, Fifth Edition, Diabetes in the Young (accessed November 16, 2011).

5 For Canada, 2005 and 2006 data were obtained by applying Statistics Canada growth rates for these years to the latest 2004 data available from the OECD. For Belgium, missing data for 2006 was obtained by projecting the most recent year of data using a 10-year average annual growth rate. We decided to use 2006 data, instead of projecting to 2009, given that for several countries there was no clear trend in the direction of growth.

6 Public Health Agency of Canada, “Mortality,” Diabetes in Canada, First Edition (Ottawa: PHAC, 1999), (accessed August 18, 2008).

7 Public Health Agency of Canada, Report from the National Diabetes Surveillance System: Diabetes in Canada, 2009 (Ottawa: PHAC, 2009), 6 (accessed November 16, 2011).

8 Ibid., 6–7.

9 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Health at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators (Paris: OECD, 2011), 43.

10 Canadian Diabetes Association, The Prevalence and Costs of Diabetes, April 2008 (accessed August 18, 2008).

11 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Health at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators (Paris: OECD, 2011), 42.

12 International Diabetes Federation, Diabetes Atlas, Fifth Edition (accessed November 16, 2011).

13 Canadian Diabetes Association, The Prevalence and Costs of Diabetes, April 2008 (accessed August 18, 2008).

14 Ibid.

15 Michael Tjepkema, “Adult Obesity,” Health Reports, 17, 3, Cat. No. 82-003 (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, August 2006), 19.

16 OECD, OECD Health Data 2011 (accessed January 11, 2012).

17 Canadian Diabetes Association, The Prevalence and Costs of Diabetes, April 2008 (accessed August 18, 2008).

18 Public Health Agency of Canada, Report from the National Diabetes Surveillance System: Diabetes in Canada, 2009 (Ottawa: PHAC, 2009), 3 (accessed November 16, 2011).

19 Canadian Diabetes Association, The Prevalence and Costs of Diabetes, April 2008 (accessed August 18, 2008).

20 Public Health Agency of Canada, “Diabetes in Canada: facts and figures from a public health perspective,” (accessed January 11, 2012).

21 OECD, OECD Health Data 2011 (accessed cited January 11, 2012).

22 Two sets of BMI measurements are available: self-reported and measured. Estimates based on self-reported height and weight are available for most countries. BMI estimates derived from actual measurements of height and weight are sparse and available only for a select number of countries—these data are generally higher and more reliable than BMI estimates based on self-reporting.

23 OECD, OECD Health Data 2011 (accessed January 11, 2012).

24 Margot Shields, “Overweight and Obesity Among Children and Youth,” Health Reports, 17, 3, Cat. No. 82–003 (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, August 2006), 38.

25 OECD, Health at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators (Paris: OECD, 2011), 57. Note: Data are not available for Austria, Belgium, and Ireland.

26 Canada Health Infoway, Multi-National Study Shows International Doctors Ahead of Canadians, Press release, July 12, 2006 (accessed cited August 18, 2008).

27 Canadian Diabetes Association, DICE Study Backgrounder (Toronto: CDA, 2005), 2.

28 Health Council of Canada, Why Health Care Renewal Matters: Lessons From Diabetes (Toronto: Health Council of Canada, March 2007), 13.

29 Canadian Diabetes Association, DICE Study Backgrounder (Toronto: CDA, 2005), 4.