GDP Growth

Key Messages

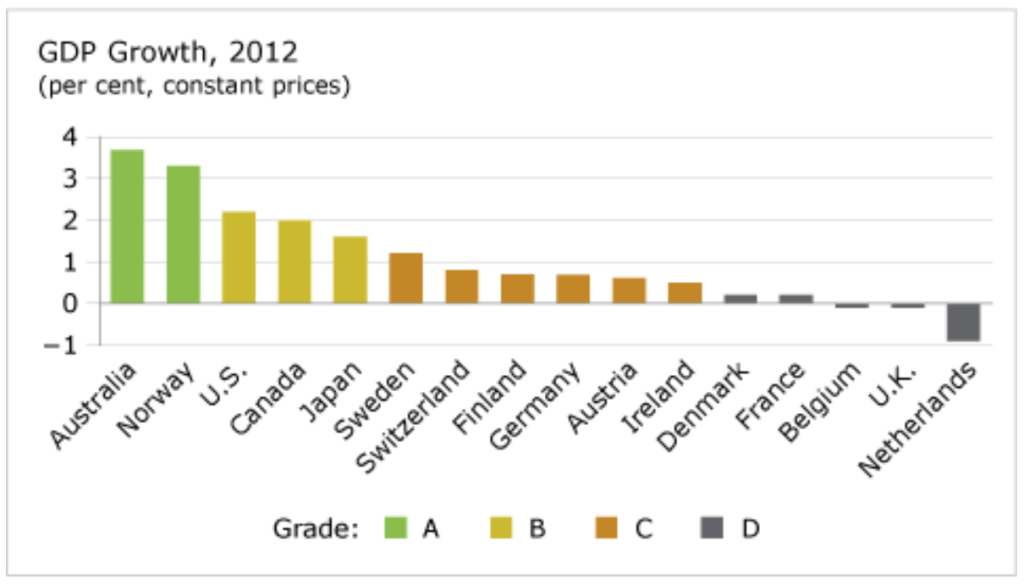

- Canada earns a “B” grade on GDP growth and ranks 4th out of 16 peer countries.

- Australia and Norway are the only two countries with an “A” for GDP growth.

- Five comparator countries, all members of the European Union, had little GDP growth or even fell into recession in 2012, thereby earning a “D”: Denmark, France, Belgium, the U.K., and the Netherlands.

Putting GDP growth in context

Gross domestic product, or GDP, is often used as an aggregate indicator of the increase in a country’s standard of living or prosperity. The numbers used in this analysis are adjusted to remove the effect of inflation on the level of GDP, producing what economists call “real” economic growth.

How does Canada’s GDP growth rate compare to that of other countries?

Among Canada’s peer countries, Canada ranked fourth in 2012, earning a “B” grade. Although Canada’s GDP growth rate was a tepid 2 per cent, many other comparator countries had even weaker growth. Members of the European Union in particular were hurt by fiscal austerity as they struggled to manage their public debt, sustain their standing in credit markets, and deal with the ongoing fiscal and credit crisis in Greece.

The #1 country—Australia—benefitted significantly from its deep trade relationship with China and other emerging Asian economies, recording a 2012 GDP growth rate more than 1.5 percentage points above Canada’s.

Who else outperformed Canada?

Norway was the other country to achieve an “A” grade for GDP growth. Norway weathered the 2008–09 financial crisis and recession better than most of its peers, and a recovery in energy demand and commodity prices helped to sustain the recovery in output. Since Norway is not a member of the European Union, it was shielded to some degree from the ripple effects of the continuing financial crisis in Greece and other heavily indebted EU countries.

In the U.S., GDP growth continued to rebuild from the deep 2008–09 financial crisis and recession, allowing the U.S. to earn a “B” grade. U.S. GDP growth could have been even stronger, but the needless debate over raising the federal debt ceiling, along with the inability to form a consensus on fiscal policy, impaired business confidence and dampened U.S. growth.

Has Canada’s report card on GDP growth improved over time?

Canada’s real GDP grew rapidly in the 1970s, averaging over 4 per cent per year and earning Canada an “A” grade—despite the recession in 1974–75.

A recession in the early 1980s and the inability to deal with mounting fiscal deficits and public debt pushed Canada’s grade on GDP growth down to a “C,” which was further downgraded to a “D” in the 1990s after the particularly tough recession of the early 1990s. However, Canada finally dealt with its fiscal challenges in the mid-1990s, creating the conditions for a more positive investment environment.

The 2000s was a more positive decade for Canada, notwithstanding the 2008–09 financial crisis and recession. Higher commodity demand and prices helped to propel Canada’s GDP growth in the 2000s. Canadian GDP growth has continued to be relatively strong during the beginning of this decade, achieving a “B” grade and ranking above most other peer countries.

Why did Japan perform so poorly in the 1990s and 2000s?

Japan has been subject to extreme shifts in economic fortune over the past two decades. In 1988, Japan’s GDP growth was 6.8 per cent. That same year, the Tokyo Stock Exchange briefly surpassed the New York Stock Exchange to become the largest in the world based on its total market capitalization. Land and house prices skyrocketed in Japan.

The 1990s opened with a collapse in stock and property prices. Economic activity stagnated through the first half of the decade. For two decades, Japan’s economy has lurched between weak recovery and stubborn and protracted recession, from which it has not yet convincingly emerged.

What brought about this dramatic reversal of fortune? Post-war Japanese industrial strategy relied heavily on strong inter-corporate linkages. The collapse of stock and property prices early in the 1990s revealed a fragile and overheated property market, as well as cross-holdings of equities that overstated the balance-sheet strength of major corporations. “Lifelong employment” in Japan became a casualty. Consumer confidence was severely eroded by employment uncertainty, shrinking asset values, and diminishing faith in banks, credit unions, and other financial intermediaries. Business confidence in Japan was undermined by the loss of traditional partnerships, declining demand, and inadequate capital.

Government efforts to revive Japan’s economic growth in the 1990s and 2000s were largely unsuccessful. Japan’s macro-economic policy mix—repeated fiscal stimulus, but tight monetary policy—did not support a sustained recovery. Japan’s stock of gross public debt is now the highest among industrial countries, exceeding 200 per cent of GDP. The tsunami and earthquakes of 2011 only added to the economic misery, breaking energy and industrial supply chains. The latest Japanese government is again trying to foster stronger growth through fiscal and monetary stimulus, but it remains unclear whether Japan can break out of its largely negative cycle.