Which Canadian province welcomes the most immigrants?

Much has been made about immigration levels in recent times, with stakeholders debating how many immigrants Canada and Quebec should welcome in the years to come. Such debates tend to focus on two metrics: the absolute number of new immigrant arrivals, and the share of new immigrants in proportion to the population.

As Canada celebrates the 20th anniversary of the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) in 2018, it is worth assessing how the provinces fare in relation to each other in terms of their immigrant intake. The obvious answer is that Ontario leads the pack. However, when we assess the second metric, the answer is likely to surprise you.

Background of Provincial Involvement in Immigration

Quebec was an immigration pioneer among the provinces. Concerned by its low birth rate and the possibility that it would see its francophone character—and demographic weight and influence—within Canada wane, Quebec launched the country’s first provincial immigration ministry in 1968 to attract more francophone newcomers. The rest of Canada’s provinces became more engaged in the immigration system in the decades to follow, with the 1990s and 2000s seeing the most intense period of provincial activity. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Federal and Provincial/Territorial Immigration Agreements

| Jurisdiction | Date agreement signed | Start of selection program |

|---|---|---|

| Quebec | February 20, 1978 | 1978 |

| Manitoba | June 28, 1998 | 1999 |

| New Brunswick | February 22, 1999 | 1999 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | September 1, 1999 | 1999 |

| Saskatchewan | March 16, 1998 | 2001 |

| Prince Edward Island | March 29, 2001 | 2001 |

| British Columbia | April 19, 1998 | 2001 |

| Alberta | March 2, 2002 | 2002 |

| Yukon | April 1, 2001 | 2002 |

| Nova Scotia | August 27, 2002 | 2003 |

| Ontario | November 21, 2005 | 2007 |

| Northwest Territories | August 7, 2009 | 2009 |

Sources: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; The Conference Board of Canada.

The launch of the Provincial Nominee Program in 1998 was one of the most important developments in Canadian immigration history. A joint initiative by the federal government and provinces, the PNP enabled jurisdictions across Canada to address their demographic and workforce needs by allowing them to shape economic class immigrant selection criteria.

At the time of the PNP’s launch, Ontario, Quebec, and B.C. dominated Canada’s immigrant intake while the Prairie and Atlantic provinces were the “have nots” of immigration. This was problematic because the Prairie provinces needed labour to support their growing economies while the Atlantic provinces needed people to alleviate their demographic challenges.

The federal government assigns PNP allocations to each jurisdiction based on its annual immigration levels planning and consultations with the provinces. (See Table 2.) The PNP has proven to be most important in the Atlantic provinces, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan—all six jurisdictions depend on the PNP for the lion’s share of their economic class immigrant arrivals. (See Table 3.) This is because the PNP allows them to specifically target immigrants that meet their needs and few immigrants selected by the federal government choose to land in these provinces.

Table 2

PNP Allocations

(principal applicants)

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 3,000 | 3,500 | 3,500 | 3,500 | 3,800 | 4,150 | 5,800 | 5,800 | 6,000 | 6,250 |

| Alberta | 4,000 | 5,000 | 5,000 | 5,000 | 5,500 | 5,500 | 5,500 | 5,500 | 5,500 | 5,600 |

| Saskatchewan | 3,400 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 4,450 | 4,725 | 5,500 | 5,500 | 5,600 | 5,750 |

| Manitoba | 4,000 | 5,000 | 5,000 | 5,000 | 5,000 | 5,000 | 5,500 | 5,500 | 5,500 | 5,700 |

| Ontario | 1,000 | ,1000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,300 | 2,500 | 5,200 | 5,500 | 6,000 | 6,600 |

| Nova Scotia | 350 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 600 | 700 | 1,350 | 1,350 | 1,350 | 1,350 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 225 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 1,050 | 1,050 | 1,050 | 1,050 |

| New Brunswick | 550 | 625 | 625 | 625 | 625 | 625 | 1,050 | 1,050 | 1,050 | 1,050 |

| Prince Edward Island | 350 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 850 | 850 | 850 | 850 |

| Yukon | 190 | 190 | 190 | 190 | 190 | 190 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

| Northwest Territories | n.a | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

| Total | 17,065 | 20,665 | 20,665 | 20,665 | 22,315 | 24,240 | 32,300 | 32,600 | 33,400 | 34,700 |

Sources: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; The Conference Board of Canada.

Table 3

Provincial Nominee Arrivals

(principal applicants and dependants, percentage of province’s total economic class arrivals)

| Province | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 0 | 0 | 23 | 19 | 26 | 50 | 38 | 32 | 28 | 34 | 55 | 52 | 69 | 72 | 79 | 74 | 78 | 69 | 63 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 63 | 76 | 87 | 93 | 96 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 97 | 93 | 93 | 95 | 95 | 98 | 94 |

| Nova Scotia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 27 | 49 | 50 | 47 | 50 | 38 | 55 | 59 | 71 | 72 | 56 | 77 | 83 |

| New Brunswick | 0 | 6 | 19 | 30 | 46 | 45 | 67 | 81 | 79 | 76 | 78 | 78 | 83 | 88 | 87 | 89 | 87 | 93 | 90 |

| Ontario | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 13 |

| Manitoba | 22 | 43 | 42 | 57 | 67 | 81 | 81 | 90 | 92 | 92 | 93 | 92 | 94 | 94 | 92 | 95 | 91 | 93 | 94 |

| Saskatchewan | 2 | 5 | 6 | 11 | 26 | 36 | 46 | 61 | 78 | 83 | 91 | 86 | 91 | 93 | 93 | 89 | 86 | 90 | 90 |

| Alberta | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 15 | 23 | 32 | 33 | 43 | 42 | 40 | 38 | 31 | 28 | 32 |

| British Columbia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 11 | 13 | 18 | 16 | 20 | 27 | 36 | 33 | 31 | 33 | 34 |

Sources: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; The Conference Board of Canada.

The PNP has been a tremendous success. Whereas Ontario, Quebec, and B.C. received 90 per cent of all of Canada’s economic class arrivals in 1999, this share has fallen to 62 per cent in 2017. (See Chart 1.) This shows the PNP is meeting its intended goal: to spread immigration’s benefits across Canada.

Chart 1

Economic class arrivals

(principal applicants and dependants)

* Newfoundland and Labrador and Prince Edward Island admitted 237 economic immigrants combined in 1999.

Sources: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; The Conference Board of Canada.

How the Provinces Rank Against Each Other

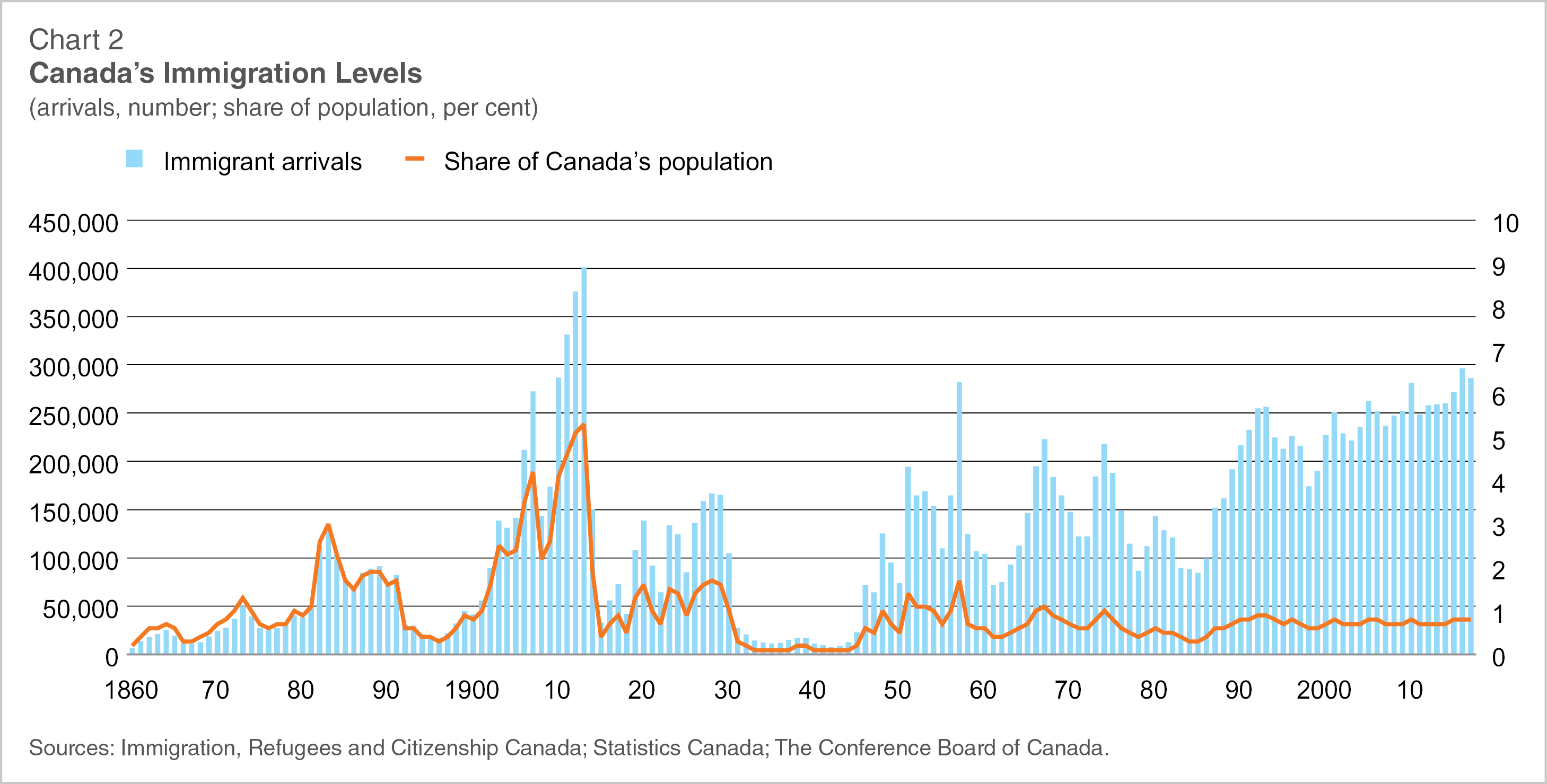

While Ontario easily welcomes the most immigrants in Canada—nearly 40 per cent of all newcomers—it lags when we assess immigration as a share of each province’s population. Nationally, Canada’s annual newcomer intake is about 0.8 per cent of the population, and this is set to rise to about 0.9 per cent under the federal government’s 2019–21 Immigration Levels Plan. (See Chart 2.)

P.E.I. leads Canada in terms of its newcomer intake as a share of its population. In 2017, it welcomed 1.64 per cent of its population in newcomers. (See Table 4.) Saskatchewan ranked second (1.34 per cent), followed by Manitoba (1.15 per cent) and Alberta (1.15 per cent). Using this metric, Ontario falls to fifth among the provinces (0.83 per cent).

Table 4

Immigration as a Share of Population

| Newcomers (2017) | Population (2016) | Percentage of population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prince Edward Island | 2,349 | 14,2907 | 1.64 |

| Saskatchewan | 14,679 | 1,098,352 | 1.34 |

| Manitoba | 14,695 | 1,278,365 | 1.15 |

| Alberta | 42,098 | 4,067,175 | 1.04 |

| Ontario | 111,923 | 13,448,494 | 0.83 |

| British Columbia | 38,447 | 4,648,055 | 0.83 |

| Quebec | 52,388 | 8,164,361 | 0.64 |

| Nova Scotia | 4,513 | 923,598 | 0.49 |

| New Brunswick | 3,649 | 747,101 | 0.49 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1,174 | 519,716 | 0.23 |

| Canada | 286,482 | 35,151,728 | 0.81 |

Sources: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; Statistics Canada; The Conference Board of Canada.

There are numerous implications from these findings, including the following:

- P.E.I.’s intake is impressive, but the province has had retention challenges due to its small population. Nonetheless, immigration is enabling P.E.I.’s population and economic growth to outpace the national average.

- One can argue that Saskatchewan and Manitoba have been the two biggest beneficiaries of the PNP. They are enjoying high levels of attraction under the PNP, as well as retention.

- While Ontario and B.C. have seen their national share of immigration decline, their intake is in line with the national per capita average.

- Quebec, on the other hand, significantly lags the national per capita average even though it welcomes the second most immigrants among all jurisdictions—its absolute and per capita intakes look poised to decline under its new immigration plan.