Futureproofing Essential Work

How vulnerable are Canada’s essential sectors to automation, migration flows, and worldwide health crises?

The pandemic has put the spotlight on the importance of workforce planning. Insights and lessons learned from COVID-19 could help employers to better prepare for the next disruption.

What Is Essential Work?

There’s no single definition. But broadly, it’s work that is instrumental to meeting the basic needs of society , like healthcare services, food manufacturing, and energy and utilities.

Public Safety Canada has a list of essential sectors and occupations to help government bodies and employers navigate the pandemic.

What’s Challenging about Essential Work?

Labour shortages

While COVID-19 shrunk labour demand in some sectors, employers felt labour shortages in others more acutely.

Labour continuity

Essential sectors faced continuity challenges in accessing labour, with significant disruptions in migration flows and increasing pressure on the existing workforce to deliver goods and services in the pandemic context.

Barriers for workers

Many essential workers face multiple barriers in the labour market due to sexism, racism, xenophobia, and other factors—and the pandemic exacerbated them.

Employment precarity

Migrant workers and temporary residents fill key labour gaps on farms. Yet farmworkers with temporary visas face significant vulnerabilities around visa status and quality of life.

Healthcare stress and burnout

Healthcare workers are facing significant mental health and well-being challenges.

Four Key Questions

The Conference Board of Canada’s knowledge areas worked together to answer four questions around futureproofing the essential workforce:

Will essential sectors and occupations face more job vacancies and skills shortages in the short term?

What role do immigrants play in essential sectors—and what role will they hold in the future?

How will automation impact essential occupations?

How can employers attract—and keep—essential workers?

Supply, Demand, and COVID-19

How has the pandemic changed worker supply and demand in essential sectors?

Here are some examples.

Nurse and residential care

Over 50 per cent of nursing homes experienced critical labour shortages in essential roles in 2020.

Agriculture

Surveys conducted by The Conference Board of Canada recently revealed that over 40 per cent of agriculture employers were unable to employ all the workers they needed in 2020.

Logistics/delivery

Over two-thirds of trucking and logistics employers were not able to fill all the driver positions they needed over the past year

We expect vacancies in these essential sectors to persist. This will hamper future growth.

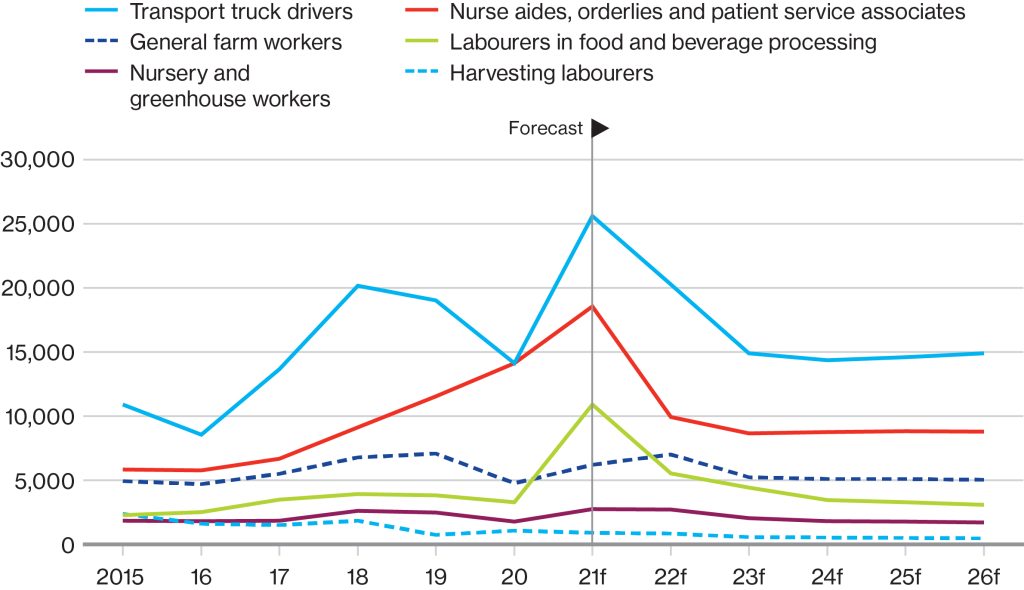

Vacancy Projections for Select Essential Occupations

(number of vacancies)

f = forecast

Note: Job titles are from the National Occupation Classification (NOC) database.

Source: The Conference Board of Canada.

Since the number of jobs shrunk in the Canadian economy during 2020—and labour demand subsequently rebounded in the short term—essential job vacancies in 2021–22 are expected to be higher than the pre-pandemic period.

According to our projections, this will be particularly noticeable for:

- Transport truck drivers

- Nurse aides, orderlies, and patient services associates

- General farm workers

- Nurse aides, orderlies, and patient services associates

- General farm workers

However, in the years leading up to 2026, essential vacancies will level off—partly due to immigration.

Immigrants in Essential Work

Essential occupations in Canada are often difficult, low-paying, and without benefits.

This discourages local workforces from seeking jobs in these industries.

Who are employers relying on to close this gap? Immigrants, newcomers, and migrant workers.

Major Issues

Over-representation

Permanent residents and naturalized citizens are over-represented in many essential sectors compared with immigrants in the overall workforce.

- 45 per cent of labourers in food and beverage processing are immigrants.

- 30 per cent of nurse aides, orderlies, and patient service associates are immigrants.

- Newcomers represent a significant proportion of Personal Support Workers (PSWs) in Canada’s care sector.

- PSWs were significantly more likely to have contracted COVID-19 compared to doctors and nurses.

Overqualification

How does overqualification impact labour shortages?

- Many immigrants have bachelor’s degrees but work in jobs that don’t require that level of education. This is common for immigrants in essential work.

- It lowers job satisfaction, which leads to more resignations and higher turnover.

- It limits immigrant earnings—and subsequently, immigrants’ economic contributions.

Filling essential jobs

How can immigrant and migrant workers find fulfilling jobs in Canada?

- Canada’s immigration system should remain responsive to labour market demand.

- Workers with different skill levels need pathways to become permanent residents.

- Employers must address bias and discrimination in recruitment and other HR practices.

The Risky Business of Automation

92 occupations in Canada are at major risk of automation.

People in these jobs have few or no options to switch to lower-risk ones without significant retraining.

These are called high-risk, low mobility (HRLM) occupations.

HRLM Jobs at a Glance

- About 3.5 million, or 1 in 5 Canadian employees, work in these roles.

- Among Canadians, equity-seeking groups are over-represented in many HRLM roles.

- Newcomers are also concentrated in HRLM roles.

- Both these groups will likely be disproportionately impacted by automation.

Essential Occupations and HRLM: What’s the Overlap?

Some essential jobs that have played a key role during the pandemic are high-risk, low-mobility.

There are also essential jobs that are not high-risk, low-mobility—in other words, not as vulnerable to automation.

Which is Which?

Next Steps

- Policymakers must craft strategies and responses that tackle the job displacement that risk workers face from automation and technological change.

- Employers will need to be part of reskilling and upskilling solutions for essential workers affected by automation.

- Employers and government need to collaborate to improve compensation and benefits in essential jobs, with the goal of boosting attraction and retention. This would help prepare essential sectors for future crises.

- Employers and government can also help expand access to mental health resources and supports.

Take a closer look at our research in immigration, automation, and the future of the Canadian workplace.

Valued Workers, Valuable Work: The Current and Future Role of (Im)migrant Talent (Impact Paper)

Responding to Automation: How Adaptable is Canada’s Labour Market? (Issue Briefing)

Working Through COVID-19: The Next Normal (Data Briefing)