Suicides

Key Messages

- With the lowest average suicide rates in Canada between 2010 and 2012, P.E.I. and Ontario earn “A” grades and outperform all but one international peer.

- Canada earns a “B” and ranks 5th among the 16 peer countries.

- Overall, Canada’s suicide rate was lower in 2012 than it was in 2000, but has been increasing since 2006.

Putting suicides in context

The World Health Organization defines suicide as the “act of deliberately killing oneself.”1 It is a “tragedy that affects families, communities, and entire countries and has long-lasting effects on the people left behind.”2 It is also a global phenomenon: over 800,000 people die by suicide every year, and many more suicides are attempted, in all regions of the world.

Suicide is a leading cause of death among young people (15 to 34 year olds) globally.3 Moreover, suicide rates are high among vulnerable populations who experience discrimination.4 Given the extent to which suicide affects communities across the globe, it is important to understand its causes and how societies can intervene to mediate its occurrence.

Common risk factors for suicide include mental disorders, particularly depression or substance abuse, and some physical illnesses. However, while the link between mental illness and suicide is well-established, not everyone who commits suicide is mentally ill. Indeed, suicide can result from many different factors, such as experiencing:

- personal crises (e.g., divorce, illness, loss of employment)

- conflict or disaster

- violence or abuse

- loss or a sense of isolation5

Suicide is a complex issue, and no one determinant alone is enough to be the cause. However, whether the above risk factors result in suicide is partly determined by the level of support a society provides toward addressing root causes, raising awareness, and investing in multi-sectoral suicide prevention strategies.

How do the provinces and Canada rank relative to international peers?

Half of the provinces rank in the top 10 among the 26 comparator jurisdictions. P.E.I. and Ontario both earn “A” grades and place among the top three overall, with average suicide rates of 7.4 and 8.7 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively, between 2010 and 2012. The U.K. has the lowest average suicide rate of all the regions at 6.8 deaths per 100,000 population.

B.C. (10.2) earns a “B” and ranks 5th, behind the Netherlands (9.6). Newfoundland and Labrador (10.6) and Nova Scotia (10.6) also earn “B” grades and tie for 7th, trailing Denmark (10.4) and placing just ahead of Germany (10.7).

Overall, Canada ranks 5th among the 16 peer countries, tied with Australia, and gets a “B” with a three-year average suicide rate of 11.0 deaths per 100,000 people, nearly double that of top-ranked United Kingdom.

Five provinces fall below the Canadian average. Manitoba’s average suicide rate is 12.7 per 100,000 population, which earns it a “B” and places it just ahead of the U.S. (12.8) in the rankings. The U.S. is followed by Saskatchewan (13.0), Alberta (13.1), and Quebec (13.2)—all three provinces earn “B” grades. New Brunswick (13.8) ranks just behind Quebec and earns a “C” grade.

The worst-ranked overall is Japan with three-year average suicide rate of 20.4 deaths per 100,000 population.

How do the provinces rank relative to each other?

P.E.I. and Ontario have the lowest suicide rates among the provinces, with rates below 10 deaths per 100,000 population.

With suicide rates ranging from 10.2 to 10.6, B.C., Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nova Scotia do better than the national average.

Half of the provinces fall below the Canadian average of 11.0 suicides per 100,000 population. New Brunswick’s suicide rate is the highest among the provinces, at 13.8 deaths per 100,000 population—over two times the rate of the top-ranked province, Prince Edward Island.

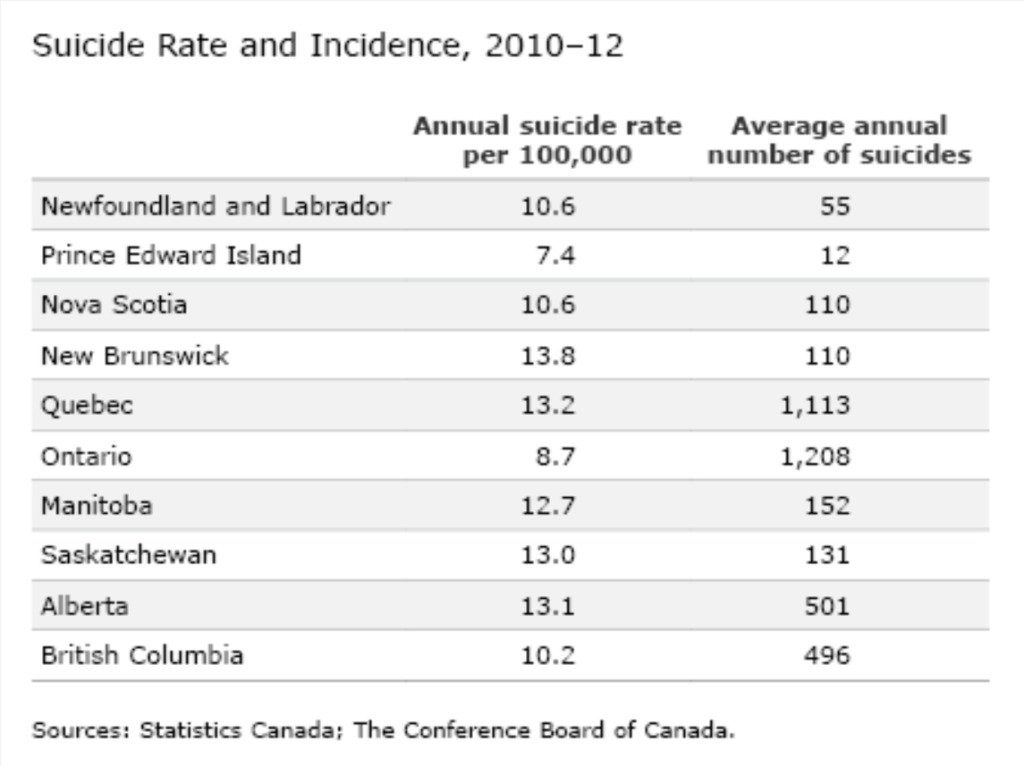

This report card looks at suicide rates and not the actual number of incidents of suicide. Thus, a high suicide rate for a province with a low population can translate into a relatively low number of actual suicides. Similarly, a seemingly low suicide rate may actually reflect a high number of suicides for a highly populated province. For example, consider top-ranked provinces P.E.I and Ontario. The average suicide rate in P.E.I. between 2010 and 2012 was 7.4 deaths per 100,000 population—this translates to an annual average of 12 suicides. Ontario had an average suicide rate of 8.7, and the annual average number of people who committed suicide in the province over this three-year period was 1,208.

This report card looks at suicide rates and not the actual number of incidents of suicide. Thus, a high suicide rate for a province with a low population can translate into a relatively low number of actual suicides. Similarly, a seemingly low suicide rate may actually reflect a high number of suicides for a highly populated province. For example, consider top-ranked provinces P.E.I and Ontario. The average suicide rate in P.E.I. between 2010 and 2012 was 7.4 deaths per 100,000 population—this translates to an annual average of 12 suicides. Ontario had an average suicide rate of 8.7, and the annual average number of people who committed suicide in the province over this three-year period was 1,208.

How do the territories rank on suicides?

The Yukon and the Northwest Territories are both “C” performers, with three-year average suicide rates of 13.9 and 16.1 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively. Both territories have average suicides rates that are higher than that of the lowest-ranked province, New Brunswick.

With the highest suicide rate among all the jurisdictions, Nunavut is a “D–” performer. The territory had an average of 65.5 suicides per 100,000 population between 2010 and 2012—over three times more than the bottom-ranked peer country, Japan.

The territories are not included in the overall benchmarking rankings because data for the territories are not available for key indicators included in the society report card. However, the Conference Board is committed to including the territories in our analysis, and so we provide information on territorial performance when data are available.

Why are the suicide rates in the territories so high?

The Aboriginal suicide rate is two to three times higher than the non-Aboriginal rate for Canada. Even more shocking, the youth suicide rate for the Aboriginal population is five to six times higher than that of non-Aboriginal youth, and rates among Inuit youth are among the highest in the world, at 11 times the national average.6 Indeed, in a report published in 2013, Statistics Canada estimated that male and female suicide rates among Aboriginal youth under 20 years of age were 30 and 25.5 per 100,000 population, respectively. These figures are especially troubling for regions where the Aboriginal population is greatest, like Nunavut and N.W.T., which have the highest suicide rates in Canada.7

Depression is the most common illness among those who commit suicide,8 and nearly two-thirds of those committing suicide in Nunavut experience a major depressive episode at some point in their lives. Of this share, almost three-quarters are also diagnosed with another mental disorder, suggesting that it might be the combination of depression and another mental disorder that leads to suicide.

Those committing suicide in Nunavut are also more likely to suffer from substance or alcohol abuse, and a high share suffered from childhood abuse. A study by McGill University and the Douglas Mental Health University Institute examined all 120 suicides in Nunavut between 2003 and 2006. Researchers reviewed medical and police records and interviewed family and friends of the victims. The study revealed high rates of childhood abuse, depression, and alcohol and marijuana abuse among the Inuit who took their lives. Among the group, 72 per cent were diagnosed with more than one mental health disorder, and almost half had experienced childhood physical, sexual, or psychological abuse. The study raised questions about the availability of psychiatric care for the group suffering from mental health disorders—82 per cent of the group had never taken medication for a mental illness, and only 17 per cent had ever been hospitalized for mental health problems.9

How have suicide rates in the provinces and territories changed over time?

Between 2000 and 2012, Canada’s suicide rate decreased overall, from 11.5 to 10.9 deaths per 100,000 population. However, within that period, the country’s suicide rate increased between 2006 and 2009, from 10.5 to 11.1, before dropping again to 10.9 in 2011.

Suicide rates in seven of the provinces decreased over 2010 to 2012. P.E.I. and Quebec had the most notable drops, with suicide rates falling by 40 per cent and 24 per cent, respectively. P.E.I.’s suicide rate dropped from 10.1 in 2000 to 6.1 in 2012.

B.C. and Alberta had more moderate decreases in suicide rates, dropping from 10.4 to 9.9 and 13.4 to 12.8, respectively. However, these decreases were due to an increase in the population and not a decrease in the number of suicides. The actual number of suicides in B.C. increased from 435 suicides in 2000 to 484 suicides in 2012. Similarly, the number of suicides in Alberta increased from 407 suicides in 2000 to 498 suicides in 2012. The same applies to Saskatchewan, which saw its suicide rate decrease from 12.6 to 12.4 between 2000 and 2012, even though the province had a higher suicide count in 2012 (126) than in 2000 (122).

Suicide rates increased in Nova Scotia, Manitoba, and Ontario between 2000 and 2012. Nova Scotia experienced the largest change in suicide rate of any Canadian jurisdiction, at an increase of 4.3 deaths per 100,000 population—from 7.2 to 11.5. The actual number of suicides in the province increased from 75 in 2000 to 118 in 2012.

Interestingly, all provinces—except New Brunswick, Quebec, and Alberta—saw an increase in their suicide rate from 2008 to 2009, which coincides with the global economic crisis, a time when personal crises (e.g., unemployment, financial losses) may have affected many Canadians. Significantly, the suicide rate peaked in 2009 (for the period of 2000–2012) for Nova Scotia, P.E.I., and Saskatchewan.

All the territories saw their suicide rates decrease overall between 2000 and 2012—despite experiencing a lot of volatility, something that is not surprising given their small populations.

Yukon saw the largest decrease in suicide rates, with an overall drop of 17 per cent, or 4.2 deaths per 100,000 population. There was much volatility in the suicide rate between 2000 and 2012, however: it halved between 2003 and 2004 and then continued to fall, reaching a low of 5.3 deaths per 100,000 in 2009, before increasing steadily to 14.3 in 2012.

The Northwest Territories experienced a similar fluctuation. Its suicide rate decreased by 2.9 deaths per 100,000 population, or 13 per cent, over 2000 to 2012. There was a large decrease (15.6 deaths per 100,000 population) in the suicide rate, from a high of 24.6 in 2004 to a low of 9 in 2005. The suicide rate continued to fluctuate up and down from 2006 onwards, but trended upwards, and was 19.2 in 2012.

Nunavut’s suicide rate fell 20 per cent between 2000 and 2012. There was a notable decrease in suicides between 2003 and 2005, when the rate decreased by 47.2 deaths per 100,000 population.

What can the provinces and territories do to decrease their suicide rates?

Strategies from the World Health Organization to prevent suicide include:10

- Include suicide prevention as a regional health priority and raise awareness about it within society.

- Reduce the stigma surrounding mental illness.

- Support early identification and treatment, and continued care, of individuals with mental illness and substance abuse disorders, chronic pain, and acute emotional distress.

- Limit access to the means of suicide (e.g., firearms, pesticides, certain medications).

- Introduce alcohol policies to curb alcohol abuse.

- Train non-specialized health care workers to identify, assess, and manage suicidal behaviour

- Improve follow-up care for individuals who attempt suicide, and provide community support.

Suicide is a complex issue. Therefore, effective prevention strategies require dedicated, coordinated, and comprehensive collaboration among multiple actors within society, including health ministries and agencies, educational institutions, businesses, law enforcement, and the media.

While Canada currently has no national suicide prevention strategy, the federal government has funded direct mental health care for targeted groups, “including Indigenous people living on reserve and in Inuit communities, serving members of the Canadian Armed Forces, veterans, current, and former members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, newcomers, and federally incarcerated individuals.”11

Over the past two decades, several provinces and territories have introduced major initiatives to curb suicide. Significantly, in 2016, two suicide prevention strategies were put in place in Canada’s Northern communities.

The Government of Nunavut, in partnership with Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, the RCMP, and Embrace Life Council, released Resiliency Within: An Action Plan for Suicide Prevention in Nunavut 2016–17. This strategy builds on previous territorial suicide prevention action plans and focuses on strengthening “meaningful stakeholder engagement and community development,”12 particularly among communities and service providers.

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the national representational organization for Canada’s 60,000 Inuit, released its National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy in 2016. This strategy is “designed to coordinate suicide prevention efforts at the national, regional, and community levels” and aims to lower suicide rates among Canada’s Inuit peoples through evidence-based, Inuit-specific actions.13

Footnotes

1 World Health Organization, Suicide.

2 World Health Organization, Suicide Fact Sheet.

3 Tanya Navaneelan, Health at a Glance, Suicide Rates: An Overview (Ottawa, Statistics Canada, 2012).

4 World Health Organization, Suicide Fact Sheet.

5 Ibid.

6 Health Canada, Suicide Prevention (accessed October 28, 2014).

7 Health Canada, National Aboriginal Youth Suicide Prevention Strategy (accessed October 28, 2014).

8 Tanya Navaneelan, Health at a Glance, Suicide Rates: An Overview (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2012.

9 Edward Chachamovich and Monica Tomlinson, Learning From Lives That Have Been Lived (Montreal: McGill University and the Douglas Mental Health University Institute, 2013).

10 World Health Organization, Suicide Fact Sheet.

11 Government of Canada, Overview of Federal Initiatives in Suicide Prevention, February 2016, 9.

12 Government of Nunavut, Resiliency Within.

13 Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy, 2016, 3.