The Future Is Social and Emotional

Evolving Skills Needs in the 21st Century

Français • April 8, 2020

Demand for skilled employees is not new, but the skills considered “in demand” have evolved.

While developing skills is a life-long endeavour, the skills that Canadians learn through post-secondary training are key to workplace success. But demand for social and emotional skills (SES) is growing. Are we doing enough to prepare Canadians for the evolving workplace?

On behalf of the Future Skills Centre, The Conference Board of Canada is examining SES and how they fit in the workplace. In this multi-year project, our team of researchers will explore the trends, challenges, and opportunities around developing social and emotional skills and what they mean for the future of work.

Skills trends in recent decades

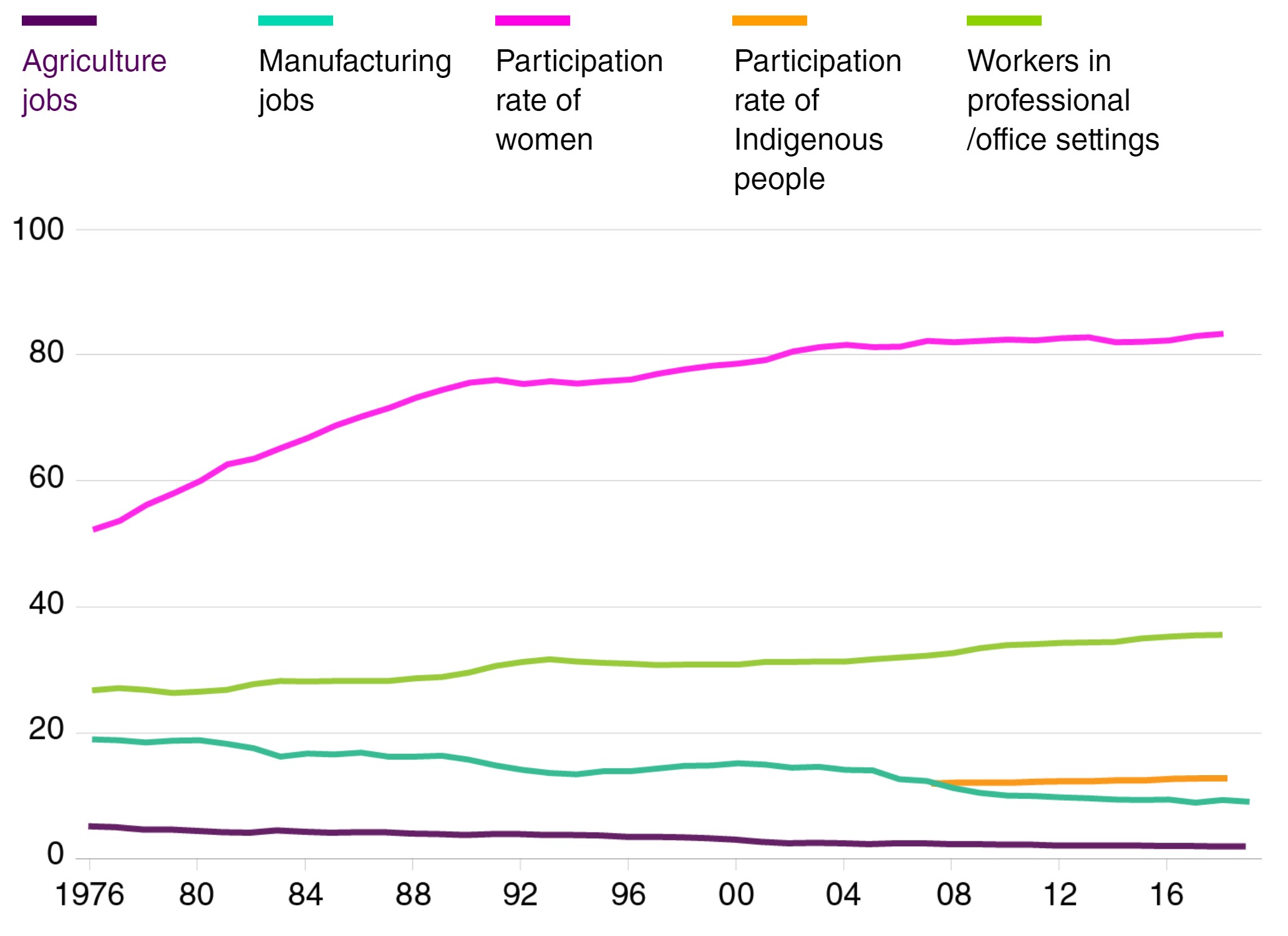

Agriculture jobs

Jobs in agriculture take a dive around the turn of the century.

Manufacturing jobs

The share of manufacturing jobs has halfed since the 1970s.

Participating rate of women

Just over half of Canadian women are engaged in the labour force in the 1970s. By the turn of the century, this rises to nearly 80 per cent and reaches 83 per cent in 2018.

Participating rate of Indigenous people

Indigenous people are joining the labour force in growing numbers as employability needs for vulnerable groups gain attention.

Note: Statistics Canada data on the Indigenous participation rate are only available starting in 2008.

Workers in professional/office settings

Growing numbers of Canadians work in business settings, as the share of the population working in manufacturing or agriculture continues to decline.

Fewer calories are being consumed from liquid refreshment beverages

(average calories per person per day)

In the post-war era, more employers seek employees with specialized knowledge in science, technology, and engineering. University enrollment increases, as does the number of people working as managers. While employers in the 1970s still largely look for analytical or technical skills, interpersonal, communication, and negotiations skills are becoming more important for managers. People are starting to think about what training for these skills might look like.

Computer technology in the workplace leads to concerns about automation, the “future of work,” and whether it will lead to “technological unemployment” (displacement due to technology).

The concept of “learning to learn” emerges, with a focus on the range of skills people need, such as literacy and “generic skills” like communication and collaboration.

By 2006, more than 80 per cent of Canadians live in increasingly diverse, multicultural cities, underscoring the need for interpersonal skills and cross-cultural competencies.

Increasingly, policy-makers are using the term “social and emotional skills.”

Emerging technologies reignite fears of automation and the displacement of workers. Social and emotional skills are consistently in demand.

Note: Professional/office includes public administration, health care and social assistance, educational services, and scientific and technical services, as defined by the North American Industry Classification System. Sources: The Conference Board of Canada; Statistics Canada. Tap here for more details.

Technological change will significantly affect the Canadian workforce.

Already, tasks once performed by humans have been automated, and many experts feel we are merely at the beginning of major transformations in the ways we work.

Researchers expect more than a quarter of jobs will be “heavily disrupted” in the next 10 years,1 while as much as 42 per cent of the Canadian labour force will be at “high risk” of being affected by automation in the next 10 to 20 years.2

While demand for workers with less training or education has fallen, in part due to globalization and automation, demand for highly educated workers with strong technical skills has risen.3

Growing demand for social and emotional skills

But in the emerging economy, technical skills are only part of the equation. More than ever, success in the workplace requires a mix of technical skills and social and emotional skills.

Social and emotional skills describe a person’s ability to regulate their emotions and behaviour, collaborate with others, build relationships, and communicate effectively. Specific in-demand skills that fall into this category include critical-thinking, resiliency, and leadership.

Sidenote

Management skills encompass a range of social and emotional and technical skills.

Employers tend to emphasize project and time management skills, though business and self-management skills are also mentioned.

The words in the illustration above represent a sample of social and emotional skills Canadian employers and HR professionals reported as in- demand in the past decade.

To communicate effectively is to share ideas or convey meaning in a simple, clear manner. This includes verbal (e.g., writing, speaking) and non-verbal forms of communication (e.g., tone, eye contact). Communication is also a two-way street: active listening and trying to understand others are critical parts of strong communication skills. Good communicators adapt to different audiences and accommodate diverse views, knowledge, perspectives, and backgrounds.

Problem-solving includes flexibility, creativity, critical thinking, and the ability to draw on different perspectives and approaches to understand problems and reach solutions. Skilled problem-solvers can look at a challenge and break it down into its parts. They ask the right questions to identify the problem and why it exists. They can brainstorm solutions, think deeply about how to find the best solutions, and evaluate the inherent risks and opportunities.

Collaboration is all about effective teamwork—how to “mesh minds” to create and achieve shared goals. Skilled collaborators seek opportunities to work with others. They appreciate the value of differing opinions and approaches and work cooperatively and constructively within teams. Empathy, problem-solving, and clear and open communication go a long way in supporting collaboration.

Resiliency is about being flexible, coping with unexpected stressors, adjusting to changing environments, and thriving through unpredictable circumstances. It’s the ability to seek appropriate supports and “bounce back” when tough times hit. Resilient people can pivot and adapt to evolving demands and the changing nature of work.

Good leaders demonstrate initiative—they are not afraid of a challenge, actively seek responsibilities, and take charge when it comes to making decisions. Leaders cultivate a collaborative and inclusive vision for their teams. They set and meet substantial goals and help others do the same. They influence and motivate their colleagues to do good work. How? By communicating openly and effectively, providing guidance, and acting with integrity and empathy—especially in the face of conflict.

Cultural competence encompasses respect for different cultural practices, as well as the willingness to understand without judgement and to adapt to various perspectives and ways of knowing. It requires a curious, empathetic, and compassionate outlook on the diverse experiences of other people. In Canada’s increasingly diverse workforce, sensitivity to cultural differences is both valuable and imperative. Cultural competence can create inclusive environments where innovative work and forward-thinking ideas can thrive.

- work ethic (willingness to learn, reliability, dedication, going the extra mile)

- critical thinking (creative thinking, critical observation)

- interpersonal skills (human skills, people skills)

- social intelligence (social skills, emotional intelligence,

social perceptiveness)

Discussions on the evolving economy and changing skills needs in Canada frequently mention leadership, resiliency, communication, collaboration, problem-solving, and interpersonal skills.

These are highly sought-after skills, but they’re tough to teach and tough to measure. As a result, they’re often overlooked in evaluating students’ success.

What’s the problem?

SES research, frameworks, and assessment tools tend to focus on the K–12 sector. How well these frameworks and tools can be adapted for post-secondary students, or adults more generally, hasn’t been established.

Most post-secondary programs tend to develop SES implicitly or indirectly (i.e., groupwork activities that strengthen interpersonal and teamwork skills), but typical methods of evaluation don’t measure the impact of these experiences. It’s often assumed, but not assessed.

This may help explain an apparent gap between the skills post-secondary programs equip students with and those that employers demand. For example, a 2018 survey of 95 large Canadian private sector employers found that, while new graduates appear to have the right foundational skills, “employers are less impressed with the human skills and basic business acumen of new graduates.”4

Social and emotional skills are malleable and can change and develop well into adulthood.

Partnerships between post-secondary institutions and businesses may be part of the solution. The Business/Higher Education Roundtable (BHER) has shown that graduates who engage in work-integrated learning activities like co-ops or internships are more likely to report that their education prepared them with teamwork, interpersonal, and communication skills, among others.

Of course, students are not alone in feeling the impacts of automation and related technologies. If the jobs of tomorrow will place greater emphasis on social and emotional skills (as a growing body of research suggests is likely), then helping adults assess and improve their skill sets is an important priority.5

Where do we go from here?

The future is social and emotional. During our multi-year project, the Future Skills Centre will:

- Clarify the state of social and emotional skills development in Canada, with a focus on adult learners across PSE institutions and beyond.

- Establish a digital knowledge hub of SES resources to serve educators, employers, and policy-makers.

- Evaluate barriers to SES learning opportunities for marginalized groups and individuals, and find testable solutions/best practices.

- Identify ways to translate research into tools that promote lifelong SES learning for both students

and employees.

Stay tuned for updates on our Social and Emotional Skills research project here

- RBC, Humans Wanted, (Toronto: RBC, 2018), accessed June 26, 2019, https://discover.rbcroyalbank.com/humans-wanted-canadian-youth-can-thrive-age-disruption/.

- Creig Lamb, The Talented Mr. Robot: The Impact of Automation on Canada’s Workforce (Toronto: Brookfield Institute for Innovation + Entrepreneurship, 2016), accessed June 27, 2019, https://brookfieldinstitute.ca/report/the-talented-mr-robot/.

- Alessandra Colecchia and George Papaconstantinou, “The Evolution of Skills in OECD Countries and the Role of Technology” (OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 1996/08, OECD Publishing, Paris, 1996), https://doi.org/10.1787/613570623323.

- Morneau Shepell, Navigating Change: 2018 Business Council Skills Survey (Toronto: Morneau Shepell and Business Council of Canada, 2018), 7–10, accessed June 27, 2019, https://www.morneaushepell.com/ca-en/insights/navigating-change-2018-business-council-skills-survey.

- Recent research from the World Economic Forum, C.D. Howe Institute, RBC, and the Institute for Competitiveness & Prosperity suggests that most job openings in the future will require aptitude in social and emotional skills.