Automation Technologies and Canada’s Labour Market

Measuring the Totality of Exposure

Français • September 24, 2025

Automation technologies present Canadian businesses with opportunities for improved productivity, labour efficiencies, and growth. Adopting these technologies will change how industries operate, including the types of jobs and skills needed. Demand for some jobs will shrink, while others will experience changes in their tasks and workflows—and not everyone will be impacted equally.

We know that change is coming. But we don’t know which jobs and industries are most likely to benefit from automation and which are most likely to be disrupted, since acceptance, expertise, regulatory frameworks, and cost will all influence how and to what degree these technologies are adopted.

On behalf of the Future Skills Centre, we have developed a framework to identify which occupations are most exposed to automation and estimate the impacts, on both workers and industries, of adopting these technologies.

This research has the potential to identify which industries and occupations are at the greatest risk of displacement or transformation and which are positioned for growth driven by technological adoption. Future research based on this framework will equip decision-makers to manage risks, capitalize on opportunities, and guide Canada’s workforce through this period of profound change. Our upcoming issue briefing on the productivity potential of automation technology will identify which industries are forecasted to benefit the most.

Measuring exposure to automation with big data

We estimated automation exposure for occupations by connecting the promise of what new technologies could do (as described in their patent applications) to the specific job tasks they could be applied to. Our exposure scores expand on existing AI-only approaches by measuring exposure to a broader set of automation technologies including AI as well as robots, autonomous vehicles and drones, virtual and augmented reality, and connected devices, allowing us to develop the most complete measure of exposure to automation.

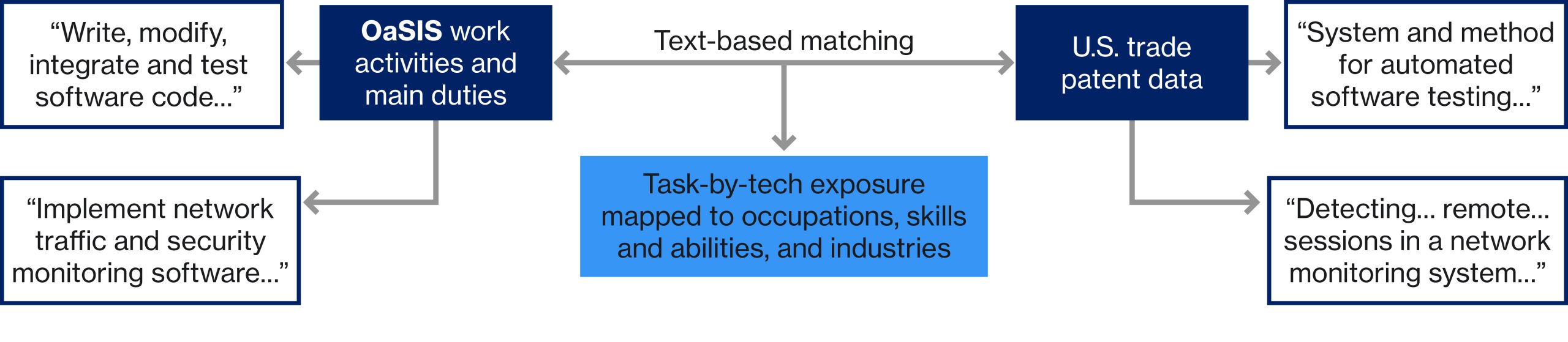

We used open-source U.S. patent data (USPTO) to identify the potential functions of these technologies and mapped them onto work descriptors in the OaSIS framework using machine-learning algorithms. (See Exhibit 1.) Through this approach, we generated 388 million technology-by-task comparisons.

Exhibit 1

Example of matches between language in a patent and work activity description in OaSIS

Source: The Conference Board of Canada

We use the only official, made-in-Canada skill taxonomy

The Occupational and Skills Information System (OaSIS) is a comprehensive Canadian dataset that captures the skills, abilities, attributes, knowledge, and interests required for more than 900 occupations.

Using these technology-by-task scores, we extrapolated to what extent the specific tasks associated with a job can be automated by one or more of these emerging technologies.

We aggregated task-level exposures to the occupation level based on both the importance of the task to an occupation and the number of patents associated with a task. The resulting Exposure Index indicates the percentage of job-specific tasks that are exposed to automation technologies for that occupation.

We then extended this metric of occupational exposure to estimate overall automation exposure by industry. Finally, to provide richer regional insights that reflect the mix of industries seen across Canada, we calculated these exposure scores for every industry and province.

Weighting occupational scores

We weighted occupational scores according to the distribution of occupations in an industry within a province.

For example, when we calculated the exposure score for transportation (the industry) in Newfoundland and Labrador, the exposure of bus drivers (the occupation) was given a weight of 0.8, because bus drivers comprise 80 per cent of employment in transportation in that province.

Automation exposure results

We found that the occupations most exposed to automation are analytical and manual jobs, such as data scientists, motor vehicle assemblers, and data entry clerks, while the least exposed occupations include ones that rely on the use of social and emotional skills, such as early childhood educators and human resource managers. (See Table 1.)

This is not to say all highly exposed occupations are at risk of being replaced by technology. Automation technologies may simply enable workers in some of these occupations to do their jobs more efficiently.

Table 1

Top 10 most and least exposed occupations

| Least exposed occupations | Exposure to all technologies (%) |

|---|---|

| Religious leaders | 4.3 |

| Court clerks and related court services occupations | 5.4 |

| Religion workers | 5.4 |

| Educational counsellors | 5.8 |

| Other support occupations in personal services | 6.0 |

| Therapists in counselling and related specialized therapies | 6.8 |

| Early childhood educators and assistants | 7.0 |

| Human resources and recruitment officers | 7.3 |

| Legal administrative assistants | 7.5 |

| Professional occupations in advertising, marketing and public relations | 7.6 |

| Most exposed occupations | Exposure to all technologies (%) |

|---|---|

| Data scientists | 78.9 |

| Motor vehicle assemblers, inspectors and testers | 78.5 |

| Construction millwrights and industrial mechanics | 70.6 |

| Records management technicians | 66.4 |

| Welders and related machine operators | 65.7 |

| Data entry clerks | 62.7 |

| Oil and gas well drillers, servicers, testers and related workers | 61.3 |

| Mechanical assemblers and inspectors | 60.9 |

| Logging machinery operators | 59.8 |

| Elevator constructors and mechanics | 59.7 |

Source: The Conference Board of Canada

Download our results

We share our scores for automation exposure at the five-digit National Occupation Classification (NOC) level for Canada. These scores reflect exposure to all technology clusters combined, linking task descriptions in the OaSIS v1.0 with USPTO patent descriptors from 2005 to 2025.

A more complete picture of labour market impacts

Our automation exposure scores provide a detailed, data-driven measure of how exposed Canadian jobs are to all kinds of automation technologies—not just generative AI. However, these scores paint only a partial picture.

An employer’s decision to adopt a technology and potentially automate work depends on the expected benefits. It is not enough that generative AI can write code; it must do so at the level of a software engineer and result in sufficient productivity gains that the employer might choose to automate some of the responsibilities associated with that job.

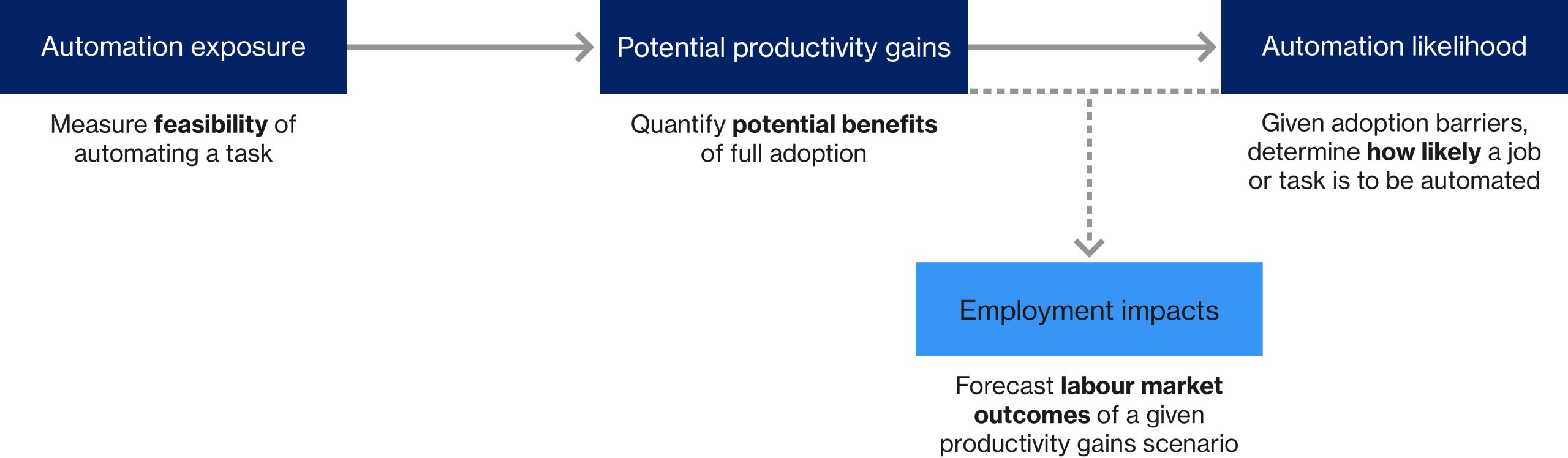

Other research in this area focuses on either the feasibility (exposure) or the probability (likelihood) of automation. Our approach distinguishes these conceptual categories and connects them through the lens of potential productivity gains. (See Exhibit 2.)

Exhibit 2

Framework to track automation technologies from potential to probability

Source: The Conference Board of Canada

Toward a more complete forecast of labour markets in Canada

Our novel combination of machine learning-driven, task-level automation analysis and productivity forecasting offers a more precise and forward-looking perspective on how automation will shape the labour market than previous research has allowed.

The next step in our research was to estimate how exposure to emerging automation technologies will affect productivity and job security. We used our industry-level exposure scores to estimate the potential gains in productivity over the next 15 years if these technologies were adopted.

These productivity estimates allow us to measure the probability of automation across occupations and industries, and are then integrated into our national economic models to generate labour-market projections for the short and long term.

We will supplement these analyses by interviewing leaders across Canada to hear more about how automation technologies are being adopted across key sectors and how they believe these technologies could impact their organizations.

Learn more

To learn more about this project, please contact Oliver Loertscher, Senior Economist.

Check out our related research in partnership with the Future Skills Centre, including our work to develop the Model of Occupations, Skills, and Technology (MOST).

This research was prepared with financial support provided through the Government of Canada’s Future Skills Program, led by our Economic Research Knowledge Area, and supported by the Education and Skills Knowledge Area. We are proud to serve as a research partner in the Future Skills Centre consortium.

FSC partners

The responsibility for the findings and conclusions of this research rests entirely with The Conference Board of Canada.