Mortality Due to Cancer

Key Messages

- Canada gets a “C” grade and ranks 13th out of 17 peer countries.

- After rising for nearly three decades, cancer mortality rates fell in Canada and in most peer countries in the 1990s.

- Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death in Canada.

Putting mortality due to cancer in context

As he set off on his “Marathon of Hope” in 1980, Canadian icon Terry Fox imagined what could happen if Canadians put their support behind cancer research. Since then, Canada has made great strides in cancer care. But unfortunately, cancer is still the leading cause of premature death in Canada. The rising number of Canadians diagnosed with cancer continues to put significant demands on health systems. Progress on preventing cancer and improving its management is still a somewhat unpredictable process, making it an ongoing health care challenge for governments at home and abroad.

The impact that cancer has on the lives of patients, their families, and the health care system cannot be overstated. The long-term emotional, physical, and psychological strain on individuals diagnosed with cancer—and their families—is profound. Just about everyone in Canada has been touched by cancer in some way. Every hour, eight people die from cancer. Each year, the number of Canadians diagnosed with cancer continues to increase.1 In 2011, an estimated 177,800 Canadians were diagnosed and 75,000 died of cancer.2

The cost of cancer care also places a heavy burden on the health care system. One estimate finds that over the next 30 years, 2.4 million workers will get cancer and 872,000 will die from the disease. Meanwhile, cancer will cost the Canadian economy an estimated $177.5 billion in direct health care costs, $199 billion in corporate profits, $250 billion in taxation revenues, and $543 billion in wage-based productivity.3

Cancer continues to exact a huge toll on the lives of Canadians; the country must not lag behind its peer countries in its efforts to reduce the incidence and mortality of cancer.

How does Canada’s mortality rate due to cancer compare to those of its peers?

Canada gets a “C” grade and ranks 13th among 17 peer countries. In 2004—the most recent year of published data for Canada—there were 169 deaths due to cancer per 100,000 population. That rate fell to an estimated 161 deaths per 100,000 population in 2009.4

The top performer—Finland—had 129 deaths per 100,000 due to cancer, while the worst performer—Denmark—had 193 people die of cancer for every 100,000 population.

Are fewer Canadians dying of cancer than in the past?

After rising for nearly three decades, deaths due to cancer fell in Canada and in most peer countries in the 1990s. The number has continued to decrease, but not as quickly in Canada as in some other countries. In 1997, for example, the U.S. and Canada experienced an almost equal number of deaths due to cancer, at 178 and 177 per 100,000 people, respectively. But the U.S. rate has since decreased much more quickly, resulting in a considerable gap between Canadian and U.S. cancer mortality rates.

Has Canada improved its relative grade?

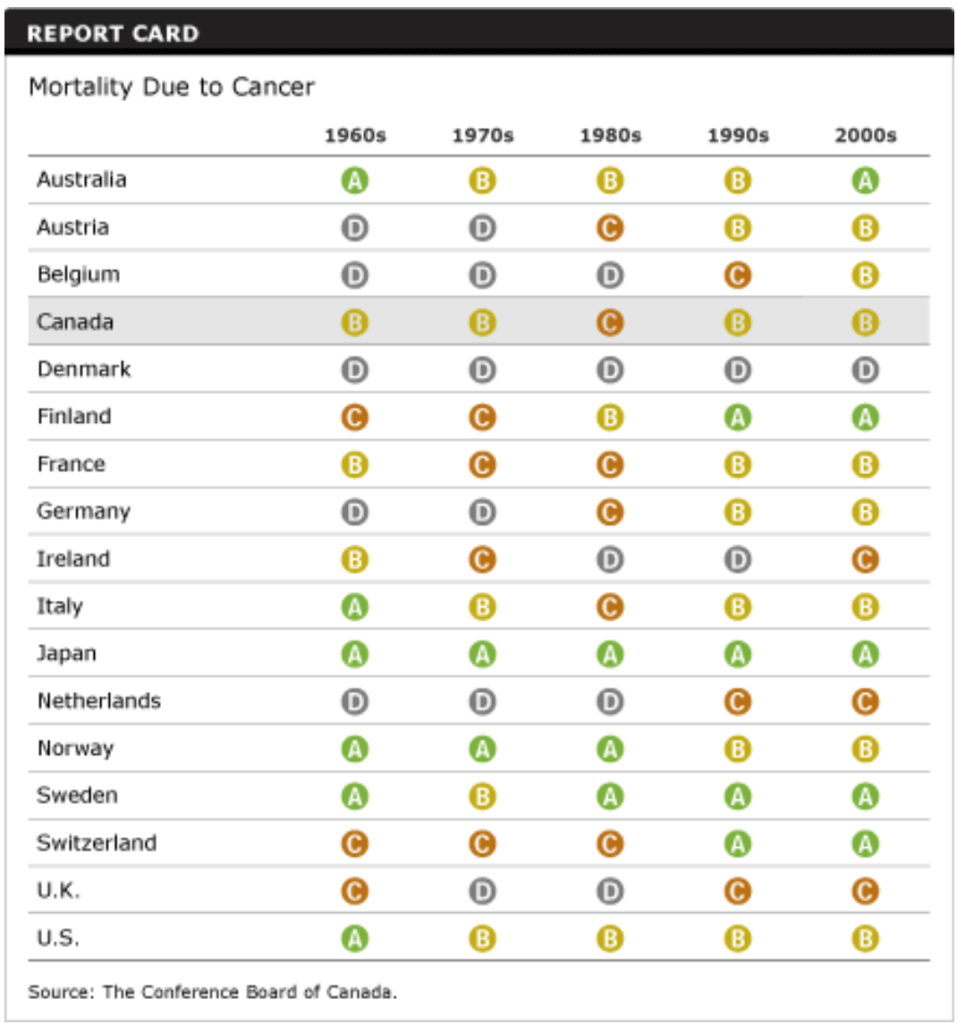

Canada’s relative grade has been fairly steady. In the 1960s, Canada’s grade on its mortality rate due to cancer was a “B.” The “A” performers were Australia, Italy, Japan, Norway, Sweden, and the United States.

In the 1980s, Canada’s grade dropped to a “C.” Canada once again earned a “B” in the 1990s and managed to maintain this grade for the 2000s overall—even though it slipped to a “C” in the most recent annual report card.

Only Japan has been a steady “A” performer over the past five decades.

The Canadian Cancer Society reports that cancer will continue to place an increasing burden on Canadian society.5 Although the cancer mortality rate has dropped, the number of new cancer cases and deaths attributed to cancer continues to rise steadily as the Canadian population grows and ages.6

Although some of the risks that lead to some cancers are well documented, other cancers (and their related risk factors) continue to be something of a mystery. Whatever the current state of research and general knowledge, Canadians need to make the link between behaviours—such as poor eating habits, weight control, inactivity, alcohol, and tobacco consumption—and cancer. Most importantly, they need to adjust their lifestyles to reduce risks.

What kinds of cancers contribute most to mortality rates in Canada?

The Conference Board examined a number of cancer mortality rates, based on health data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). These indicators give us a crude measure of the “cancer landscape” in Canada and can help to gauge Canada’s performance in relation to other countries.

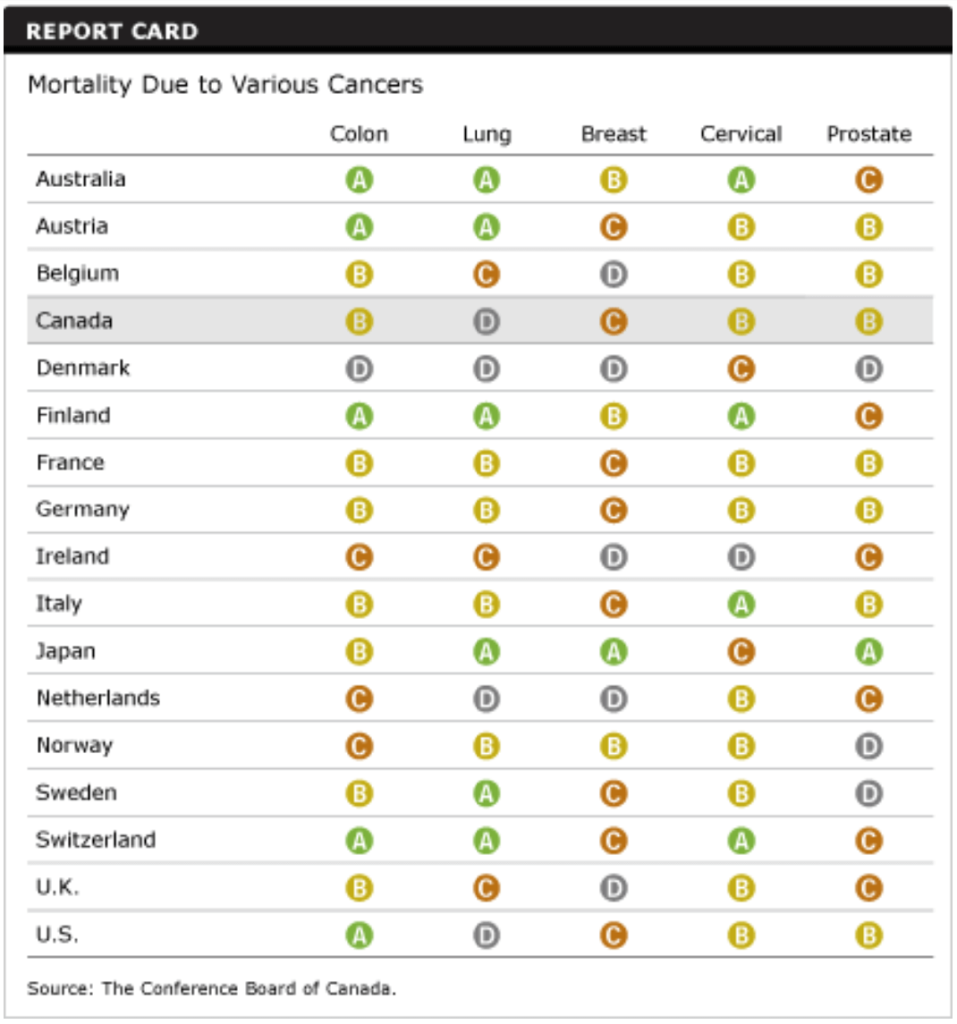

Canada is a “B” performer on mortality due to colon, cervical, and prostate cancer but only a “C” performer on deaths due to breast cancer.

The effects of Canadians’ past smoking habits are reflected in the high number of deaths from lung cancer, earning Canada a “D” on this indicator. Paradoxically, Canada also has one of the lowest smoking rates among peer countries. This underlines that there is often a long interval between exposure to risk factors such as smoking and the point at which a cancer is detected. For more on the relationship between tobacco consumption and lung cancer, see our study of the relationship between lifestyle factors and health outcomes.

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death in Canada, accounting for 28 per cent of cancer deaths in men and 27 per cent in women.7 According to the Canadian Cancer Encyclopedia, the probability of dying from lung cancer is 1 in 13 for men and 1 in 17 for women.8

While lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths in women, the incidence of breast cancer—that is, the number of new cases diagnosed—is nearly double that of the incidence of lung cancer.9

Among men, the Canadian Cancer Society has found that lung cancer rates levelled off in the mid-1980s and have been declining since, reflecting a drop in tobacco consumption that began in the mid-1960s.10 As a result, prostate cancer is now the most prevalent form of cancer among men.11

Does Canada have adequate resources for cancer diagnosis and treatment?

Canada ranks below its peers12 when it comes to the number of MRI units available per population—MRI is an important diagnostic tool for many cancers. However, simply increasing the number of MRI units will not necessarily boost Canada’s ability to diagnose and treat cancer.

At around 1 per 1,000 people, the number of general practitioners in Canada is slightly higher than the 15-country average.13 General medical practices and primary health care are the foundation for preventing and screening for chronic diseases like cancer—something that was recognized through the federal government’s Primary Health Care Transition Fund, which helped fund the transitional costs of introducing new approaches to primary health care. More timely, comprehensive, and appropriate primary health care and the use of information and communication technologies—such as electronic health records—will be key to the success of Canada’s cancer control efforts.

The number of specialists per population is below the 15-country average.14 The low number of specialists in Canada may signal a shortage of oncologists to treat cancer. The OECD, however, does not track data at this level of detail, making it difficult to compare countries.

In addition to having enough primary and specialist health care providers, Canada needs to ensure they are working together, and that they have access to the tools that will allow them to increase productivity (working smarter, not harder).

What is Canada doing to reduce the number of cancer deaths?

In its Progress Report on Cancer Control in Canada, Health Canada contends that the future of cancer control must include a commitment to:

- health promotion, prevention, and screening programs

- better national and provincial planning and integration

Canada must also commit to the research and development of more effective technologies for cancer treatment.

The 2006 federal budget confirmed the Government of Canada’s commitment to implementing the Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control. This five-year, $260-million investment was intended to improve screening, prevention, and research, and to help coordinate activities among provinces, territories, and Canada’s leading cancer organizations.15

In 2010, the Canadian Cancer Research Alliance—an alliance of cancer research funding organizations—released the first pan-Canadian Cancer Research Strategy, “a framework to guide cancer research investment in Canada and a vision for Canadian cancer research achievements over the next five years.”16 The Alliance held an inaugural conference in November 2011 to showcase Canada’s cancer research projects, connect funders to researchers, and demonstrate the impact of cancer research investment in Canada.17

Canadian researchers are hosting the World Cancer Congress for the first time in Canada in August 2012. The Congress is held every two years and provides a platform for researchers from the international cancer community to connect and share ideas.18

Individual provinces are taking action as well. Cancer Care Ontario’s Report on Cancer 2020 presents an action plan for cancer prevention and detection. The Cancer Quality Council of Ontario has established a cancer system quality index that provides a snapshot of care under the following quality dimensions: safe, efficient, effective, equitable, accessible, integrated, and responsive.19 This will help the province benchmark its progress toward cancer control.

In Alberta, as part of its 2008 Health Action Plan, the province expanded its cancer screening programs for cervical, breast, and colectoral cancer. 20

As Terry Fox envisioned, Canada has made much progress in the area of cancer detection and therapy. But there is still more work to do. Canada needs to:

- do research to develop a better understanding of the unique causes of each type, grade, and stage of cancer

- advance the use and development of screening and detection tools

- develop better management and self-management programs built on an extensive data warehouse (including new indicators suggested by the OECD)21

- improve the uptake of innovative technologies

- make the receipt of disease-specific funding contingent on the investment of these funds in a broad chronic disease strategy22

- ensure there is an adequate supply of scientific talent in key areas including genomics, proteomics, and nanotechnologies

Footnotes

1 Canadian Cancer Society, Canadian Cancer Statistics 2011, May 2011, 15 (accessed January 25, 2012).

2 Ibid.

3 Paul Smetanin and Paul Kobak, Interdisciplinary Cancer Risk Management: Canadian Life and Economic Impacts (Toronto: RiskAnalytica, 2005), (accessed February 9, 2012).

4 Missing data up to 2009 were obtained by projecting the most recent year of data using a 10-year average annual growth rate. This was done for Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States.

5 Canadian Cancer Society, Canadian Cancer Statistics 2011, May 2011, 39 (accessed January 25, 2012).

6 Ibid., 34.

7 Ibid., 15.

8 Canadian Cancer Society, Canadian Cancer Encyclopedia, “Lung Cancer” (accessed January 25, 2012).

9 Canadian Cancer Society, Canadian Cancer Statistics 2011, May 2011, 16 (accessed January 25, 2012).

10 Ibid., 37.

11 Ibid., 18.

12 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD Health Data 2011.

13 Ibid. Data are not available for Denmark and Japan.

14 Ibid. Data are not available for Denmark and Japan.

15 Canadian Cancer Society, Canada Takes Action Against Cancer (accessed September 23, 2009).

16 Canadian Cancer Research Alliance, “About Us” (accessed February 8, 2012).

17 Canadian Cancer Research Alliance, “The Canadian Research Conference,” January 2012, 1 (accessed February 8, 2012).

18 World Cancer Congress (accessed February 8, 2012).

19 Cancer Quality Council of Ontario, “Cancer System Quality Index” (accessed February 8, 2012).

20 Government of Alberta, Health Initiatives in Alberta (accessed August 26, 2009).

21 An OECD expert panel recently recommended including an extra 13 indicators in its data sets. Those related to cancer include breast cancer survival, mammography screening, cervical cancer survival, cervical cancer screening, colorectal cancer survival, incidence of vaccine-preventable diseases, and smoking rates.

22 Peter Sargious, “Chronic Disease Prevention and Management,” Health Canada, Primary Health Care Transition Fund, March 2007, 12 (accessed September 23, 2009).